Advocacy in Action: Ryan Prior

Stephanie and Ryan in Missoula

My friend Ryan takes 20 pills a day to stay well. I heard him tell this to crowds of attentive listeners several times over the weekend. “I give myself one shot a week,” he added, “and get an I.V. treatment once a month.” I watched him take the pills a few times. He carries them around in a large backpack, in one of those containers, separated out by the days of the week. The green one makes him grimace. I don’t ask what they are.

I’d sent Ryan a message on Facebook several months ago after someone who knew him encouraged me to. I’d watched Ryan’s documentary, Forgotten Plague, about his disease twice in one week. The scenes with my friend Whitney, bent over in his bed, ribs showing, long fingers covering his face, and his scraggly hair emblazoned with a patch of sun, froze the tears in my eyes, planted my hand to my mouth, and made me an activist for myalgic encephalomyelitis, the disease so clearly killing a person I loved.

Still image from Forgotten Plague

When Ryan visited Jamison for the film, Jamison still lived alone. He could sometimes do the dishes. He laughed. He did a few pushups to show how fast his heartbeat escalated, like he’d just sprinted a mile. When Ryan returned several months later, Jamison sat through the interview. He looked defeated. I wonder sometimes if he knew how bad he’d get. If he thought his trajectory was inability to speak.

I don’t know how many pills Whitney’s prescribed. His dad patiently grinds them in a marble bowl meant for spices, then mixes it with the liquid food they’ll pump into the tube surgically placed in his stomach. I watched his father Ron, a world-renowned scientist, thoughtfully stand at the end of the kitchen island at night, pausing in crushing the pills to look up at nothing. Maybe he thought of a new piece to the puzzle of his son’s disease that he researches full-time to find a cause and cure, or maybe he found the right place to put one.

Photo courtesy of Jamison Hill

Jamison used to be a body builder. He lost the ability to speak for a year and a half. “He’s almost as bad as Whitney,” people had said, because he also couldn’t chew or sit up in bed. Whitney hasn’t spoken in almost four years. Hasn’t tasted food in at least two. But Jamison came out of it from heavy doses of saline through an I.V., and can tolerate flashes of light and laughing and sitting up. When Jamison first sent me an email to share a story he’d written about it all, I couldn’t help but believe Whitney would someday do the same.

Almost every patient I talk to says these words: When I get better. A form of faith I doubt I could match, and inspires me daily.

The other night Ryan said in front of a group of students, nodding to me, that I was close to Whitney when he could still walk and talk. I’d never thought of it that way. I don’t want this part of his life to be “after.” I hope for it to be the middle. Whitney didn’t just walk and talk. He danced. He climbed to places he wasn’t allowed. He stood, thoughtfully, just like his father, seeing the world framed in a photographic lens.

None of the patients I know think they’ll ever be as bad as Whitney, and I’m not sure Whitney knows he’s the worst. He must know it’s bad, especially on Monday—the day I flew to D.C. to protest—when they had to rush him to the hospital to repair a hole in the tube that gives him food. I know he feels alone in the prison his body has trapped him in. I know this because his mom tells me he cries all the time and she can’t comfort him by touch or word, but only by placing her hand on her heart before leaving him be.  I walked around the United States capitol with Ryan for a few hours before the protest. It was hotter than I thought it’d be, and sweat dripped down my back into the waistband of my jeans. Ryan had changed into a dark shirt before we left, and he fought to keep the sleeves rolled above his elbows. I kept looking for signs he’d had enough. But ever the tour guide, he showed me the town he loved, walking me to the Library of Congress, and through the stuffy viewing platform. We paused to buy food and sat to eat it on a shady bench. We walked down past the Smithsonian, the Washington Memorial, gazed at the Whitehouse from outside the fence with the cops behind us yelling at tourists to behave. We stopped for souvenirs before sitting on the cool floor in the corner of the Lincoln Memorial. I remembered how the statue had been like a giant when I saw him at seven. How I’d looked up so far the back of my head touched my shoulders a little. Now I understood the weight of the words behind him.

I walked around the United States capitol with Ryan for a few hours before the protest. It was hotter than I thought it’d be, and sweat dripped down my back into the waistband of my jeans. Ryan had changed into a dark shirt before we left, and he fought to keep the sleeves rolled above his elbows. I kept looking for signs he’d had enough. But ever the tour guide, he showed me the town he loved, walking me to the Library of Congress, and through the stuffy viewing platform. We paused to buy food and sat to eat it on a shady bench. We walked down past the Smithsonian, the Washington Memorial, gazed at the Whitehouse from outside the fence with the cops behind us yelling at tourists to behave. We stopped for souvenirs before sitting on the cool floor in the corner of the Lincoln Memorial. I remembered how the statue had been like a giant when I saw him at seven. How I’d looked up so far the back of my head touched my shoulders a little. Now I understood the weight of the words behind him.

Ryan speaking to a group of visiting interns from the University of Georgia in Washington, D.C.

Ryan spoke a bit at the protest for his disease not even an hour later. I wondered how many times he’d done that. “I’ve lived in five states this month,” he said to a group of students a few hours later. His advocacy work had brought him to Chicago, Palo Alto, my town of Missoula, and Washington, D.C., where we held informational signs about those who suffer from the disease. Hashtagged MillionsMissing, the protest took place across 24 cities on four different continents that day.

I insisted on buying Ryan a fancy dinner after his final talk—the third in two days—and we walked through the dark streets of upscale neighborhoods to an oyster bar. Ryan went from gleefully tasting oysters from different coasts, ordering beer and a porterhouse, to excusing himself quickly. He returned to the table rubbing his eyes and couldn’t finish his meal. Within a few minutes, I’d paid the bill and gotten a car to take us home.

He said at least he’d probably sleep well that night. I wondered if he really would. I wondered if he was okay. Earlier that night, on the way to dinner, I’d told him I hadn’t thought he’d be able to do so much. I guess I wasn’t sure what to expect. Everyone who has the disease is affected differently, but most aren’t able to leave the house or even bed very much. Many hide their disability, spending the weekends recovering, not able to muster up the energy to shower.

Ryan calls himself one of the 10-15% of those who have recovered, as long as he takes those 20 pills a day. As long as he knows when to leave the restaurant and go straight home, and does.

Jamison and I texted later that night, after I dropped Ryan off. I tend to send him a photo of my glass whenever it has Jameson whiskey in it. I wrote for a little while at a bar before deciding I wasn’t writing anything. I couldn’t fall asleep; woke up groggy, dehydrated, and a little hungover. I figured Ryan probably felt the same without the aid of vices or lack of water or sleep. He sent a text and said he felt energized from getting out and walking, and I wondered if he said that so I wouldn’t worry. He swore he didn’t, but I knew if I were him I would have lied to me.

He sent me a few happy texts throughout the day, like Jamison always does. Sometimes late at night I send Whitney’s mom a text with a simple, red heart. Code. For love for each other we cannot explain. And the fiercest love for Whitney we hope he can feel.

For more information on myalgic encephalomyelitis, and to donate to fund research for treatment, go HERE.

step.

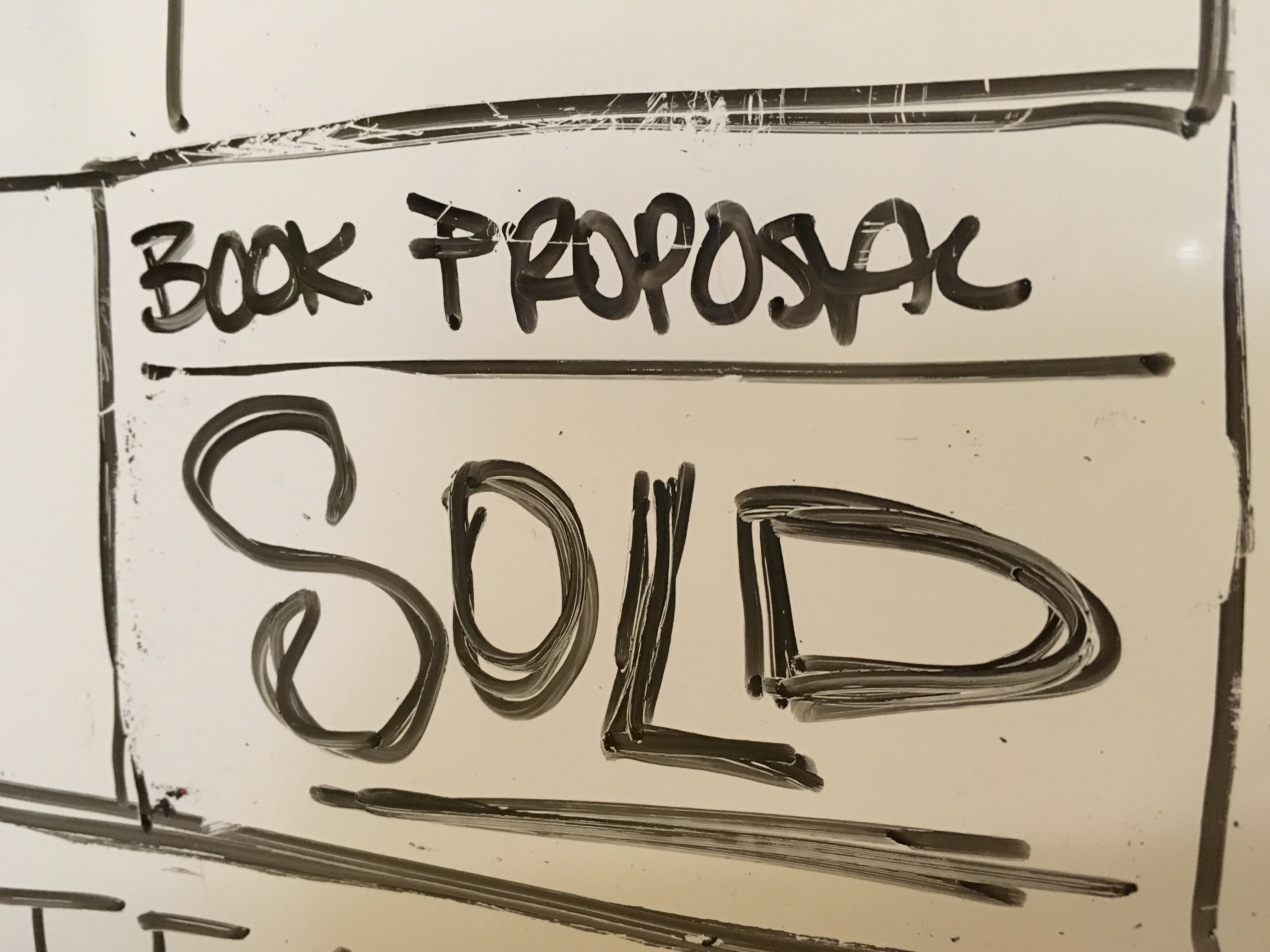

Exactly 11 months after my essay about cleaning houses was published on Vox and went viral, I accepted the offer for my memoir—an expansion of that essay. For months, I’d spent what I felt were luxurious hours not writing for pay, but working, quietly at night, with a sleeping baby in my lap, crafting the perfect book proposal with my agent, Jeff Kleinman at Folio. It felt incredibly strange to be going after something I’d wanted since I was ten years old, and at first, I didn’t have much faith in it. For over twenty years, I had been writing, reading, and studying the art of writing. It was shocking to even have an agent.

Exactly 11 months after my essay about cleaning houses was published on Vox and went viral, I accepted the offer for my memoir—an expansion of that essay. For months, I’d spent what I felt were luxurious hours not writing for pay, but working, quietly at night, with a sleeping baby in my lap, crafting the perfect book proposal with my agent, Jeff Kleinman at Folio. It felt incredibly strange to be going after something I’d wanted since I was ten years old, and at first, I didn’t have much faith in it. For over twenty years, I had been writing, reading, and studying the art of writing. It was shocking to even have an agent. I would work on that essay for the next two years, chiseling away at it little by little. When Vox bought it for $500, I about fell over. It seemed a massive amount of money, especially since I had spent the last eight years on assistance programs, and my current hourly wages from various freelancing jobs were about $10.00. I thought it would surely be the most I’d ever receive for my writing. When the essay went viral, with almost 500,000 hits in the span of three days, my career took off. Within two months, accepted a position as a writing fellow with the Center for Community Change, and had several more pieces published, including one through Barbara Ehrenreich’s Economic Hardship Reporting Project.

I would work on that essay for the next two years, chiseling away at it little by little. When Vox bought it for $500, I about fell over. It seemed a massive amount of money, especially since I had spent the last eight years on assistance programs, and my current hourly wages from various freelancing jobs were about $10.00. I thought it would surely be the most I’d ever receive for my writing. When the essay went viral, with almost 500,000 hits in the span of three days, my career took off. Within two months, accepted a position as a writing fellow with the Center for Community Change, and had several more pieces published, including one through Barbara Ehrenreich’s Economic Hardship Reporting Project. With that,

With that,  A couple of weeks after I accepted the offer, Krishan and I spoke again on the phone. “I just have to tell you,” she said. “Our office, our floor, is all open. When we received the news that you’d accepted our offer, everyone jumped up from their desks to cheer, and started hugging each other. Even the CEO of the company came out to give me a hug. I’ve never seen anything like that in publishing before. It was amazing.”

A couple of weeks after I accepted the offer, Krishan and I spoke again on the phone. “I just have to tell you,” she said. “Our office, our floor, is all open. When we received the news that you’d accepted our offer, everyone jumped up from their desks to cheer, and started hugging each other. Even the CEO of the company came out to give me a hug. I’ve never seen anything like that in publishing before. It was amazing.”