Minimalism: A Movement for the Elite

I write this just 60 minutes after finally putting my 2-year-old to bed. After putting away the toys, dishes, and giving my dog some much-needed affection. Even though it is closing in on 4AM, I am sitting at my desk instead of getting into bed. I know I won’t sleep.

For most of the evening I held my daughter as she threw up. When she finally closed her eyes and slept in my arms, I sat up, scared to leave her on the couch so I could rest in bed, and scared to put her in bed with me in fear she’d puke in my hair. And now I know that even if I do try to sleep next to her, I’ll be jarred awake every time she coughs, which she does a lot, since she’s been doing that all week at night. Only now, I’ll panic that she’s throwing up again.

But tonight, as she slept in my arms, I finally watched the new documentary about Minimalism.

I’d been putting this off. I probably wouldn’t have even watched it, but I engaged in a debate on a friend’s Facebook thread over the last couple of days, furthering the point I made in an article in The New York Times that minimalism is classist.

After watching the documentary, I realize now more than ever that I am a minimalist in nature. When I moved out on my own as a teenager, then moved dozens of times through my twenties, I gradually whittled my belongings down to what could fit in my truck, which, at the time, was a Toyota Landcruiser from the late 80s. I prided myself in this. The things I had were of value, if only to me. I was never a materialistic kind of person who needed a ton of shoes or clothes. I had books and journals. My rule was that, if I didn’t need to use something through four seasons, then I probably didn’t need it. (I made an exception for outdoor gear.) I constantly culled out shirts and pants. I rarely bought new clothes. If I brought something in, I put two in the donate bin, and so on.

Having a child a decade ago changed that. I needed household furniture. I needed a couch, a table, and a few other things to make a house a home. At the time, I worked as a maid in houses of people who were what I considered to be very wealthy, even though they weren’t super rich by most standards. They had homes like the ones that I’d grown up in in the middle class with separate dining rooms, living rooms that were hardly used, and sometimes an extra room meant for an office. Some of these places were lavish with extra rooms for doll collections or garages just for recreational vehicles–all things I saw collected enough dust that 1) the people who owned them worked many long hours to afford them and 2) didn’t have time to clean so 3) spent money for me to come in and clean.

It didn’t seem to me that these people were necessarily happier because they had these homes. When I looked at what my daughter and I had–a small studio with what we absolutely needed and not much else–the simplicity of that seemed, well, simpler, but also happier. Yes, I, too, worked long hours, but it wasn’t to afford the stuff, it was to afford our $550 a month rent. I worked long hours because I wasn’t paid much–just over minimum wage.

Minimalism preaches mindfulness in purchases, and it makes me think to the times I spent hours mulling over my Amazon cart full of Christmas presents for my daughter. I could barely afford anything, so the things I purchased had to be well thought-out and few. Buying anything for our home meant toiling over what I absolutely needed vs. what I wanted, and I hardly ever bought the latter. More so, I held on to things because I couldn’t afford to replace them. A cheap, 10 dollar set of pots and pans lasted me nearly 7 years.

When I wrote the article last Spring, it was in reaction to the documentary’s trailer, which showed scenes of people rushing box stores on Black Friday as a reason for needing this movement, or part of it anyway.

My first thought was “Those are poor people. They don’t need to hear about minimalism. Their homes and the lives they live are minimal enough.” Now that I’ve watched the entire documentary, I feel the poor-shaming even more. Those scenes are shown almost as comic relief, with circus-like music played with it, between testimonies of (usually) white men who had corporate jobs saying their lives were miserable despite having a house full of things.

In one scene, Joshua Fields Millburn reads a poem he wrote, talking about the things he needed to buy when he moved. He listed off things that I would never have dreamed of affording. Things that seemed ridiculous, as a poor person, to even consider purchasing. I’d never stepped foot into an IKEA. I’d never known rugs for decoration. Rugs were to keep feet warm, if I was lucky enough to find someone who could give me one they no longer used. But there he stood, complaining about the ability, the privilege, to buy these things.

Living in small spaces forces you to only keep things that have purpose, often multiple ones at that. This is a poor person’s way of life. The reason those people are rushing in mobs to buy a television or toy is the sales are low enough for them to afford them, and they have often saved up to do so. They will bring that item home like a prize. It will distract them from the crushing hopelessness they feel on a daily basis. Sometimes by the hour as they lie awake at night, adding up money coming in vs. money that needs to go out. A poor person’s accounting that goes down to the cent.

To tell that person they don’t need it would not only be a waste of time, but trite. Like a person who’d just eaten at a nice restaurant telling someone at McDonald’s they don’t need to supersize. Just because you have the means to afford more, just because you have the privilege to say no out of a philosophy you preach, doesn’t give you the right to tell someone counting their pennies to afford a special treat that they don’t need it while hoping they will buy your book instead. Hoping they pay to take your online class. Hoping they purchase something that will profit you.

The Minimalists strive for quality over quantity. As a person in poverty, I could only afford the cheapest clothes. Even used clothing was too expensive, and I often found myself shopping at Walmart’s clearance sales for my daughters. I wore my work pants out until my company told me I needed new ones, and to replace those was a hardship.

So yes, I write this post in the middle of the night, arguably now early hours of the morning. I write it out of anger. I notably write it as a person who considers themselves a minimalist. But most importantly, I write this as a person who has lived in poverty, who was forced to unload carloads of family heirlooms in a donation box because I didn’t have the space to keep them at a time I needed them most to remind me, as a new single mom, that I wasn’t alone.

Sometimes, us folks in poverty need to know that. That we’re not the only ones in this fight for survival. Because, you see, we can’t choose to give up lavish lifestyles and instead spend money on experiences, or going out to eat with friends. So please, all I ask is that you don’t pull poor people into your philosophy, your conversation, and especially don’t shame us. Don’t point to us as a need for a movement you wish to profit from.

-step.

Jamison later explained that he’d been in a cave for the last 18 months, unable to tolerate daylight, clothing, speaking, or chewing. Coming out of it through saline IV treatments was a rebirth. Even though he had a chance at a new life, he was still unable to sit up in bed. But he could make sounds that people understood. He could eat food. He could communicate with people through email and text.

Jamison later explained that he’d been in a cave for the last 18 months, unable to tolerate daylight, clothing, speaking, or chewing. Coming out of it through saline IV treatments was a rebirth. Even though he had a chance at a new life, he was still unable to sit up in bed. But he could make sounds that people understood. He could eat food. He could communicate with people through email and text. So we smiled at each other. I hugged him a bunch, and held his hand. We made jokes, told a few dating horror stories, and then it was time for me to give him a break.

So we smiled at each other. I hugged him a bunch, and held his hand. We made jokes, told a few dating horror stories, and then it was time for me to give him a break. “He just wants to see your faces again,” his mom said. So we stood there, blowing kisses, waving, watching him do it in return from his dark room. The cave. For the next day, as I told him I was on my way to the airport he’d text “Damn. Don’t go.”

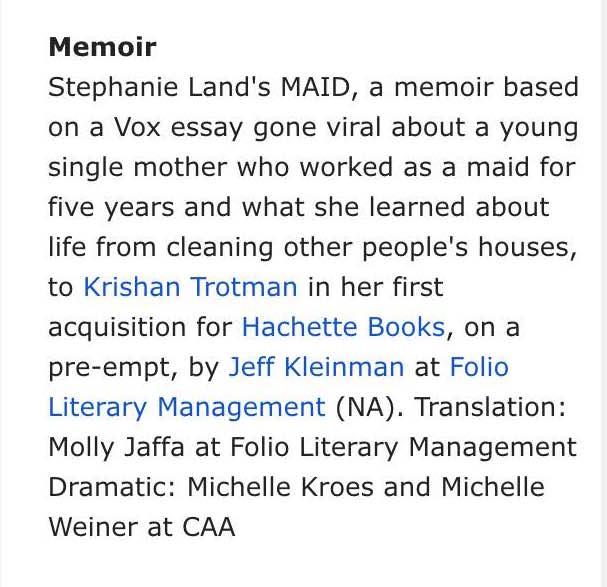

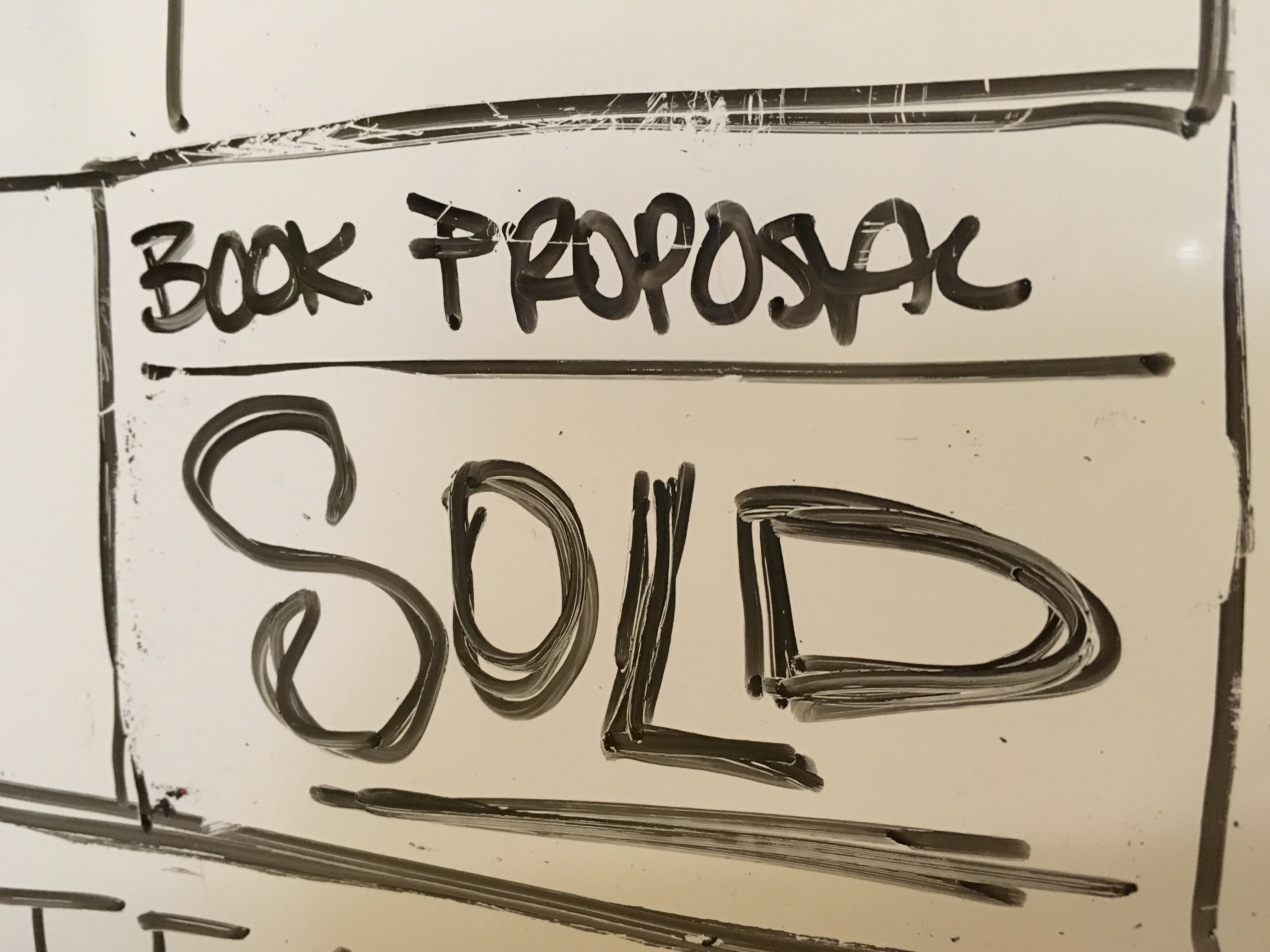

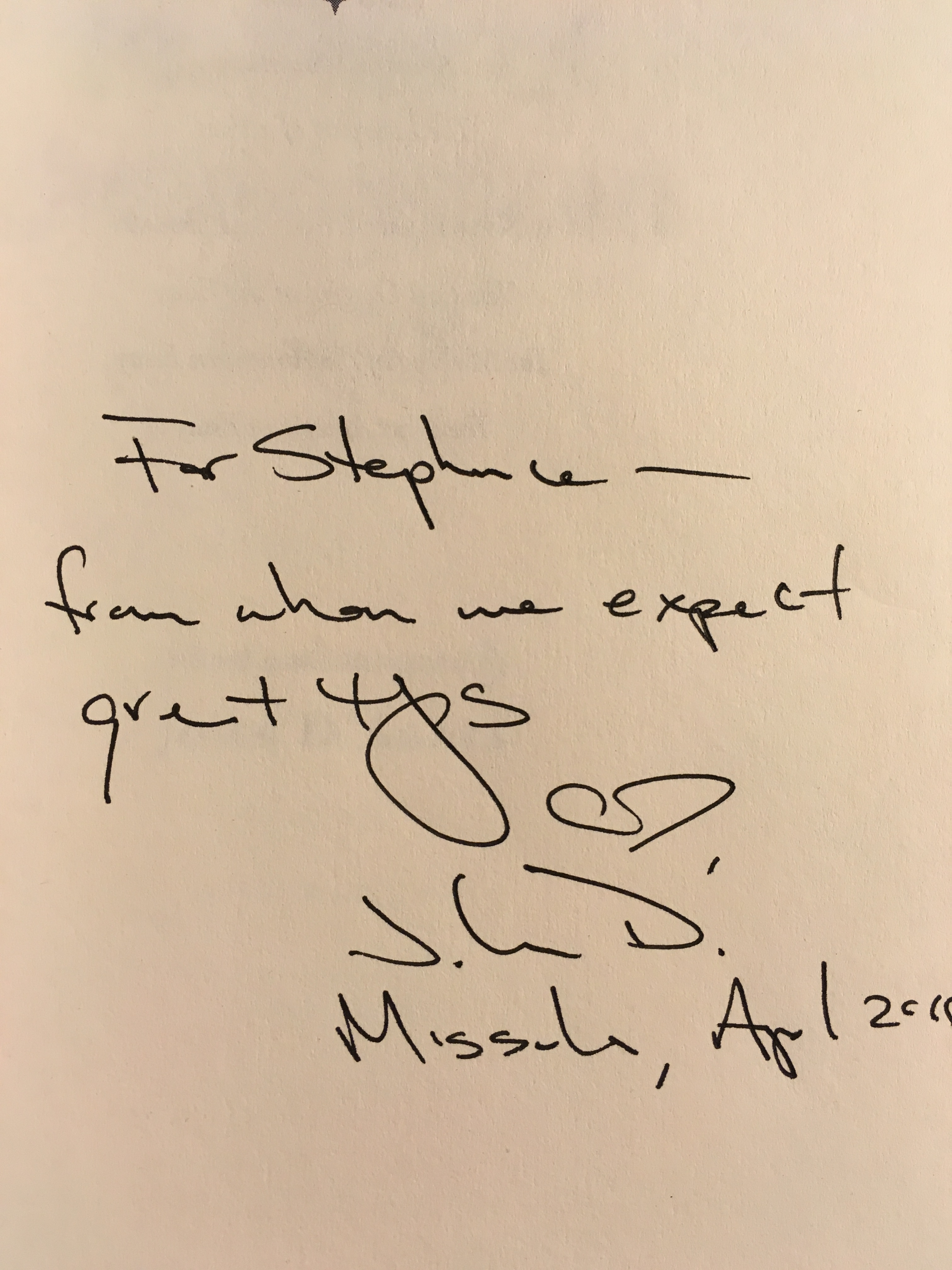

“He just wants to see your faces again,” his mom said. So we stood there, blowing kisses, waving, watching him do it in return from his dark room. The cave. For the next day, as I told him I was on my way to the airport he’d text “Damn. Don’t go.” Exactly 11 months after my essay about cleaning houses was published on Vox and went viral, I accepted the offer for my memoir—an expansion of that essay. For months, I’d spent what I felt were luxurious hours not writing for pay, but working, quietly at night, with a sleeping baby in my lap, crafting the perfect book proposal with my agent, Jeff Kleinman at Folio. It felt incredibly strange to be going after something I’d wanted since I was ten years old, and at first, I didn’t have much faith in it. For over twenty years, I had been writing, reading, and studying the art of writing. It was shocking to even have an agent.

Exactly 11 months after my essay about cleaning houses was published on Vox and went viral, I accepted the offer for my memoir—an expansion of that essay. For months, I’d spent what I felt were luxurious hours not writing for pay, but working, quietly at night, with a sleeping baby in my lap, crafting the perfect book proposal with my agent, Jeff Kleinman at Folio. It felt incredibly strange to be going after something I’d wanted since I was ten years old, and at first, I didn’t have much faith in it. For over twenty years, I had been writing, reading, and studying the art of writing. It was shocking to even have an agent. I would work on that essay for the next two years, chiseling away at it little by little. When Vox bought it for $500, I about fell over. It seemed a massive amount of money, especially since I had spent the last eight years on assistance programs, and my current hourly wages from various freelancing jobs were about $10.00. I thought it would surely be the most I’d ever receive for my writing. When the essay went viral, with almost 500,000 hits in the span of three days, my career took off. Within two months, accepted a position as a writing fellow with the Center for Community Change, and had several more pieces published, including one through Barbara Ehrenreich’s Economic Hardship Reporting Project.

I would work on that essay for the next two years, chiseling away at it little by little. When Vox bought it for $500, I about fell over. It seemed a massive amount of money, especially since I had spent the last eight years on assistance programs, and my current hourly wages from various freelancing jobs were about $10.00. I thought it would surely be the most I’d ever receive for my writing. When the essay went viral, with almost 500,000 hits in the span of three days, my career took off. Within two months, accepted a position as a writing fellow with the Center for Community Change, and had several more pieces published, including one through Barbara Ehrenreich’s Economic Hardship Reporting Project. With that,

With that,  A couple of weeks after I accepted the offer, Krishan and I spoke again on the phone. “I just have to tell you,” she said. “Our office, our floor, is all open. When we received the news that you’d accepted our offer, everyone jumped up from their desks to cheer, and started hugging each other. Even the CEO of the company came out to give me a hug. I’ve never seen anything like that in publishing before. It was amazing.”

A couple of weeks after I accepted the offer, Krishan and I spoke again on the phone. “I just have to tell you,” she said. “Our office, our floor, is all open. When we received the news that you’d accepted our offer, everyone jumped up from their desks to cheer, and started hugging each other. Even the CEO of the company came out to give me a hug. I’ve never seen anything like that in publishing before. It was amazing.” I brought my girls into this world promising them I’d take good care of them. I grew them and birthed them with hope they would prosper in our community and wherever they decided to go as adults. I made a choice as a woman, as a single woman at that, to take on this responsibility of providing them with the basic needs of food, shelter, love, and safety.

I brought my girls into this world promising them I’d take good care of them. I grew them and birthed them with hope they would prosper in our community and wherever they decided to go as adults. I made a choice as a woman, as a single woman at that, to take on this responsibility of providing them with the basic needs of food, shelter, love, and safety.

A living room free of dust and a hallway mirror without spots wasn’t out of my want to have a clean space, but my biological need to provide a safe home for my children.

A living room free of dust and a hallway mirror without spots wasn’t out of my want to have a clean space, but my biological need to provide a safe home for my children. As a mother, I sometimes resist the complete and total surrender that comes with caring for my children. I also fight to make sure I can say to them sincerely, honestly, and openly “I chose to have you because I wanted you, and I have never regretted that decision.”

As a mother, I sometimes resist the complete and total surrender that comes with caring for my children. I also fight to make sure I can say to them sincerely, honestly, and openly “I chose to have you because I wanted you, and I have never regretted that decision.” When Mia was little, I lived in close proximity to her dad, and she saw him every other weekend. Even though this wasn’t the best situation for us for various reasons, it still afforded me time off, and a back-up person if I really needed one. Though I never went anywhere, I did get a chance to catch up on homework, work extra hours, and recover from my life as a single parent. I could date. I could go out. I could even, you know, have a guy sleep over.

When Mia was little, I lived in close proximity to her dad, and she saw him every other weekend. Even though this wasn’t the best situation for us for various reasons, it still afforded me time off, and a back-up person if I really needed one. Though I never went anywhere, I did get a chance to catch up on homework, work extra hours, and recover from my life as a single parent. I could date. I could go out. I could even, you know, have a guy sleep over. I spent the next few days sending possibly hundreds of texts to arrange a schedule involving seven people. It was too late to board the dog. I found a place for Cora to go during the day, and a pet-sitter to come hang out with my anxious dog for a little while at noon. I devised an insane schedule that included people Cora didn’t know all that well. She’d be shuffled several times a day, and spending the nights at my house with her dad, who lately has had a difficult time getting Cora to sleep. Mia would also be shuffled around from school and with the neighbor and was pretty much in charge of caring for the dog in the morning and at night.

I spent the next few days sending possibly hundreds of texts to arrange a schedule involving seven people. It was too late to board the dog. I found a place for Cora to go during the day, and a pet-sitter to come hang out with my anxious dog for a little while at noon. I devised an insane schedule that included people Cora didn’t know all that well. She’d be shuffled several times a day, and spending the nights at my house with her dad, who lately has had a difficult time getting Cora to sleep. Mia would also be shuffled around from school and with the neighbor and was pretty much in charge of caring for the dog in the morning and at night. Mornings have been different lately. We all get up together, and if Cora is extra grumpy, Mia and I switch duties. While I am outside, waiting for the dog to sniff out a good spot to pee and poop, Mia is inside, getting Coraline out of her rumpled, just-slept-in-pajamas, changes her diaper, and puts her in an extra-cute outfit for daycare. I hear them laughing and singing as I walk back inside, a sharp contrast to mornings when Mia was in Kindergarten, when

Mornings have been different lately. We all get up together, and if Cora is extra grumpy, Mia and I switch duties. While I am outside, waiting for the dog to sniff out a good spot to pee and poop, Mia is inside, getting Coraline out of her rumpled, just-slept-in-pajamas, changes her diaper, and puts her in an extra-cute outfit for daycare. I hear them laughing and singing as I walk back inside, a sharp contrast to mornings when Mia was in Kindergarten, when

For the next couple of weeks, Coraline started daycare full-time, and I worked a staggering amount. In the week I had the reporter and photographer from the newspaper come interview me, I wrote about 11,000 words. I didn’t think of this as “writing.” This was producing.

For the next couple of weeks, Coraline started daycare full-time, and I worked a staggering amount. In the week I had the reporter and photographer from the newspaper come interview me, I wrote about 11,000 words. I didn’t think of this as “writing.” This was producing.

There is beauty, of course. There are moments of laughter and joy. There are friends who check in, who come over to talk, who invite one or both of my children over to play.

There is beauty, of course. There are moments of laughter and joy. There are friends who check in, who come over to talk, who invite one or both of my children over to play. Being a mother is also something I do very well, but I can’t say it’s my passion. I don’t enjoy playing, or going to parks or story time at the library. Although I am a good mother, it’s not because I mother my children directly all the time. I outsource my mothering duties. As a single mother especially, there’d be no way I could possibly be everything to my children all the time. I’d have nothing left of me. I’d have no career. My life requires a rotating, constant set of characters that step in to replace me for a time, or I would surely dissolve.

Being a mother is also something I do very well, but I can’t say it’s my passion. I don’t enjoy playing, or going to parks or story time at the library. Although I am a good mother, it’s not because I mother my children directly all the time. I outsource my mothering duties. As a single mother especially, there’d be no way I could possibly be everything to my children all the time. I’d have nothing left of me. I’d have no career. My life requires a rotating, constant set of characters that step in to replace me for a time, or I would surely dissolve. I always return to that quote by Joseph Conrad. He focused on the rivets, saying it was the little things that made all the difference. An article published on a platform I’ve pined for, being fully present while my toddler goes down a slide, laughing with a friend: they’re the little moments that keep the ship together, and chugging up the river.

I always return to that quote by Joseph Conrad. He focused on the rivets, saying it was the little things that made all the difference. An article published on a platform I’ve pined for, being fully present while my toddler goes down a slide, laughing with a friend: they’re the little moments that keep the ship together, and chugging up the river. My tax refunds have, historically, been spent in the most practical ways possible. I pay off my most high-interest debt, buy much-needed pants or shoes, get the girls a fancy dress, and usually do one shopping trip that is basically replenishing all our toiletries and medicine cabinet. This year I decided to invest, instead, in a little peace of mind.

My tax refunds have, historically, been spent in the most practical ways possible. I pay off my most high-interest debt, buy much-needed pants or shoes, get the girls a fancy dress, and usually do one shopping trip that is basically replenishing all our toiletries and medicine cabinet. This year I decided to invest, instead, in a little peace of mind.

This morning, I decided to get some groceries after dropping Coraline off at daycare. I grabbed the bigger cart, the produce section glowed, and they had a lot of great deals on meat. I ended up grabbing a lot more than I intended.

This morning, I decided to get some groceries after dropping Coraline off at daycare. I grabbed the bigger cart, the produce section glowed, and they had a lot of great deals on meat. I ended up grabbing a lot more than I intended. Cora’s clothes are on a shelf in my closet. Her socks are in the top drawer of the pink dresser in my room. For daycare, she needs what’s in the black bag in the bin next to the kitchen table. They go outside, so she needs a warm coat and boots.

Cora’s clothes are on a shelf in my closet. Her socks are in the top drawer of the pink dresser in my room. For daycare, she needs what’s in the black bag in the bin next to the kitchen table. They go outside, so she needs a warm coat and boots.