Sometimes You Go To California

On Tuesday night of this week I stood at a podium in front of a class of about 40 students. In my hands I held out a printed copy of the essay I’d recently had published through the Longreads blog about Whitney Dafoe. It wouldn’t be the first time I’d read it out loud. I’d practiced over a dozen times in the previous few weeks. My voice shook, even when I was alone in my apartment, and sometimes my eyes stung and watered.

“This piece is really raw for me right now,” I said. I didn’t say why, and instead started to read. I would have to explain that I’d been at Whitney’s house the day before. That I saw in a book a photo I’d taken in Alaska of him standing on his work truck to take a picture. That over the weekend, I’d seen his mother burst into tears over hearing the lyrics of a song. And through it all had known, once again, that he had no idea I was there. I’m sure I would have lost my composure halfway through.

Photo courtesy of the Davis-Dafoe family.

Every time I looked up, I saw blank faces, mouths agape, and one student was audibly crying. I felt horrible, but owned my decision to read the essay. I force ME/CFS in people’s faces so that, someday, it won’t be a depressing conversation.

I’d gained a new person to carry constantly in my pocket that weekend. Jamison Hill and I had been friends through email and text for several months, and a large part of my trip to California was the chance to meet him in person.

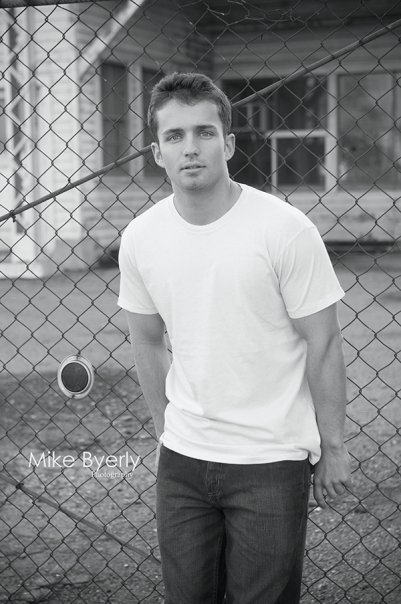

Photo courtesy of Jamison Hill

Jamison, for those who are unfamiliar, was featured in my friend Ryan Prior’s Forgotten Plague along with Whitney. Jamison’s the one in the documentary’s trailer who’s laughing, his dimples going deep into his cheeks, his bright blue eyes shining despite being one of the millions missing from ME/CFS. It’s been six years since, right around Thanksgiving, that Jamison went to the gym early in the morning like he always did, and couldn’t finish a workout he normally did thoughtlessly. His story is one of the terrifying ones: he went from being a physical trainer, a model, an amateur body builder, and otherwise active 22-year-old college student to in bed, sick, getting rapidly worse in a matter of years.

Before Jamison submitted a story for me to publish at the Blue Ribbon Foundation’s “Share your Story” section, I’d only heard that he’d become as bad as Whitney. I’d seen GoFundMe fundraisers to help with housing, medical expenses, and treatment. When Ryan spoke of him, his voice grew soft; a tone I’d come to recognize in the ME/CFS community as a person who’d taken a turn for the worse. A person who was living a form of death.

Jamison later explained that he’d been in a cave for the last 18 months, unable to tolerate daylight, clothing, speaking, or chewing. Coming out of it through saline IV treatments was a rebirth. Even though he had a chance at a new life, he was still unable to sit up in bed. But he could make sounds that people understood. He could eat food. He could communicate with people through email and text.

Jamison later explained that he’d been in a cave for the last 18 months, unable to tolerate daylight, clothing, speaking, or chewing. Coming out of it through saline IV treatments was a rebirth. Even though he had a chance at a new life, he was still unable to sit up in bed. But he could make sounds that people understood. He could eat food. He could communicate with people through email and text.

I knew most of this through reading a lot of what he’d written, but to see it was something else entirely. Ashley, Whitney’s sister, drove me, my daughter Mia, and Janet, Whitney’s mom, to Jamison’s house three hours east. We arrived at sunset, enamored with the view from the porch. Janet was the first one to go in and visit with Jamison. I was the second.

Before going back to his room, I was worried what germs I might have on my clothes. A simple cold virus could knock him down further. I was worried seeing me would cause him to crash. But mainly I was worried that he’d go beyond his limits and wake up the next morning feeling horrible and unable to move.

When I read what Jamison wrote about meeting me in his blog, what stuck out the most was that he’d hoped seeing him, smiling and sitting up would give us, his largest group of visitors in years, a new hope for Whitney.

But Jamison’s just like that. He’s easily one of the happiest, lovable humans I know. In the months of us emailing and texting back and forth, he’s gone into frustrated rants maybe twice. And a few times I had to specifically ask for them. Seeing him, sitting there, knowing he hadn’t gotten out of bed in almost two years, I was completely in awe of his ability to maintain any semblance of who he’d been six years earlier.

So we smiled at each other. I hugged him a bunch, and held his hand. We made jokes, told a few dating horror stories, and then it was time for me to give him a break.

So we smiled at each other. I hugged him a bunch, and held his hand. We made jokes, told a few dating horror stories, and then it was time for me to give him a break.

We texted late into the night. I kept asking him the next day if he felt all right. He said yes, and said he wanted to see us again. So I bought him some tea from his favorite little shop, and some fudge. We drove up to his house at sunset again, and took some pictures on the porch. I went inside to use the bathroom, and snuck across the hall to Jamison’s room.

He had thick blankets on the windows and the lights off. I couldn’t see anything, then saw the faint light of the screen of his phone–his signal to tell me where he was. I saw his shape then. He wasn’t sitting up. He was on his left side, bent over almost in a fetal position, his cheek pressed against the bed. Crashed.

I felt his hand reach out for mine and sank to my knees at the same time. My other arm went around his back, my right cheek on his head. He only had boxers on with a sheet covering his legs and feet. His mom came in to open the curtains all the way so we could see each other. I stayed that way for a bit, whispering that he should have told me he had what ME/CFS patients call “the world’s worst hangover.”

He wanted to know how long we were staying, and where we were going next, and, of course, offered ideas of where to go eat dinner. He couldn’t talk like he did the day before. Most of this I either figured out through pantomime or he had to type out on his phone.

I went in the second time after everyone else had visited to kneel down by his bed to say goodbye. He held my hand tighter, and whispered “I’m so tired of this shit.” I told him I think about him constantly. That I love him. And that I’d miss him dearly. That I’d be back to visit as soon as I could to be there more than just an hour or two. “I’ll spoon you next time,” I said, and he chuckled.

I stood out in the living room, watching Janet hug Jamison’s mom, Kathleen. “We have amazing sons,” Janet said. They were crying. A stark contrast to the night before, when we’d been celebrating recovery. Kathleen went in to check on Jamison and he wanted us all to come back, stand in the hallway, and wave goodbye one more time.

“He just wants to see your faces again,” his mom said. So we stood there, blowing kisses, waving, watching him do it in return from his dark room. The cave. For the next day, as I told him I was on my way to the airport he’d text “Damn. Don’t go.”

“He just wants to see your faces again,” his mom said. So we stood there, blowing kisses, waving, watching him do it in return from his dark room. The cave. For the next day, as I told him I was on my way to the airport he’d text “Damn. Don’t go.”

From the moment I’d left the hallway of his room I hadn’t wanted to. I didn’t want to drive away from Whitney’s house, watching Janet and Ron wave goodbye. It’s a different sort of grief, to feel too helpless, too far away, and isolated.

After I read the essay the next night, one of the students asked me if I had any advice on writing. I told them what everyone says: to sit in a chair and motherfucking write. But the next day Jamison reminded me of the necessary part that needs to exist before that.

“There is only one thing you should do,” Rilke wrote. “Go into yourself. …confess to yourself whether you would have to die if you were forbidden to write. This most of all: ask yourself in the most silent hour of your night: must I write? …if you meet this solemn question with a strong, simple ‘I must,’ then build your life in accordance with this necessity…”

Jamison writes everything on his phone. He can’t use a laptop, can’t stand looking at the screen. He wrote the last bit of his book looking at his phone through tanning goggles. That amount of passion, that desire to write words, humbles me. Even though I am finishing this post in the chaos of bedtime with a two-year-old on the floor tearing apart paper and throwing markers, it would take a crazy amount of passion for me to write this out on my phone. I’ve written in journals since I was 10 years old, and I deeply admire Jamison’s amount of “must” to write. To live.

step.

I walked around the United States capitol with Ryan for a few hours before the protest. It was hotter than I thought it’d be, and sweat dripped down my back into the waistband of my jeans. Ryan had changed into a dark shirt before we left, and he fought to keep the sleeves rolled above his elbows. I kept looking for signs he’d had enough. But ever the tour guide, he showed me the town he loved, walking me to the Library of Congress, and through the stuffy viewing platform. We paused to buy food and sat to eat it on a shady bench. We walked down past the Smithsonian, the Washington Memorial, gazed at the Whitehouse from outside the fence with the cops behind us yelling at tourists to behave. We stopped for souvenirs before sitting on the cool floor in the corner of the Lincoln Memorial. I remembered how the statue had been like a giant when I saw him at seven. How I’d looked up so far the back of my head touched my shoulders a little. Now I understood the weight of the words behind him.

I walked around the United States capitol with Ryan for a few hours before the protest. It was hotter than I thought it’d be, and sweat dripped down my back into the waistband of my jeans. Ryan had changed into a dark shirt before we left, and he fought to keep the sleeves rolled above his elbows. I kept looking for signs he’d had enough. But ever the tour guide, he showed me the town he loved, walking me to the Library of Congress, and through the stuffy viewing platform. We paused to buy food and sat to eat it on a shady bench. We walked down past the Smithsonian, the Washington Memorial, gazed at the Whitehouse from outside the fence with the cops behind us yelling at tourists to behave. We stopped for souvenirs before sitting on the cool floor in the corner of the Lincoln Memorial. I remembered how the statue had been like a giant when I saw him at seven. How I’d looked up so far the back of my head touched my shoulders a little. Now I understood the weight of the words behind him.

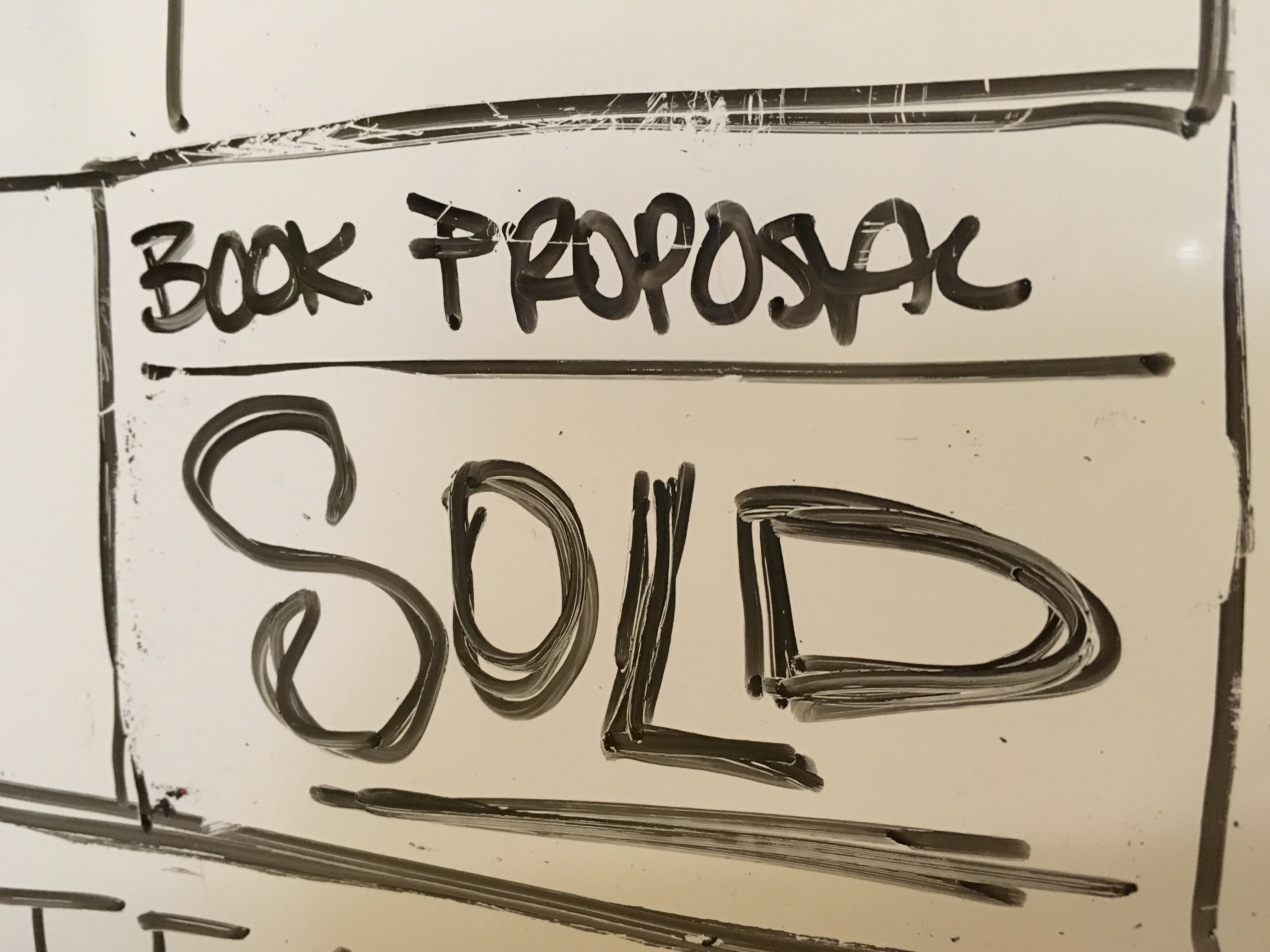

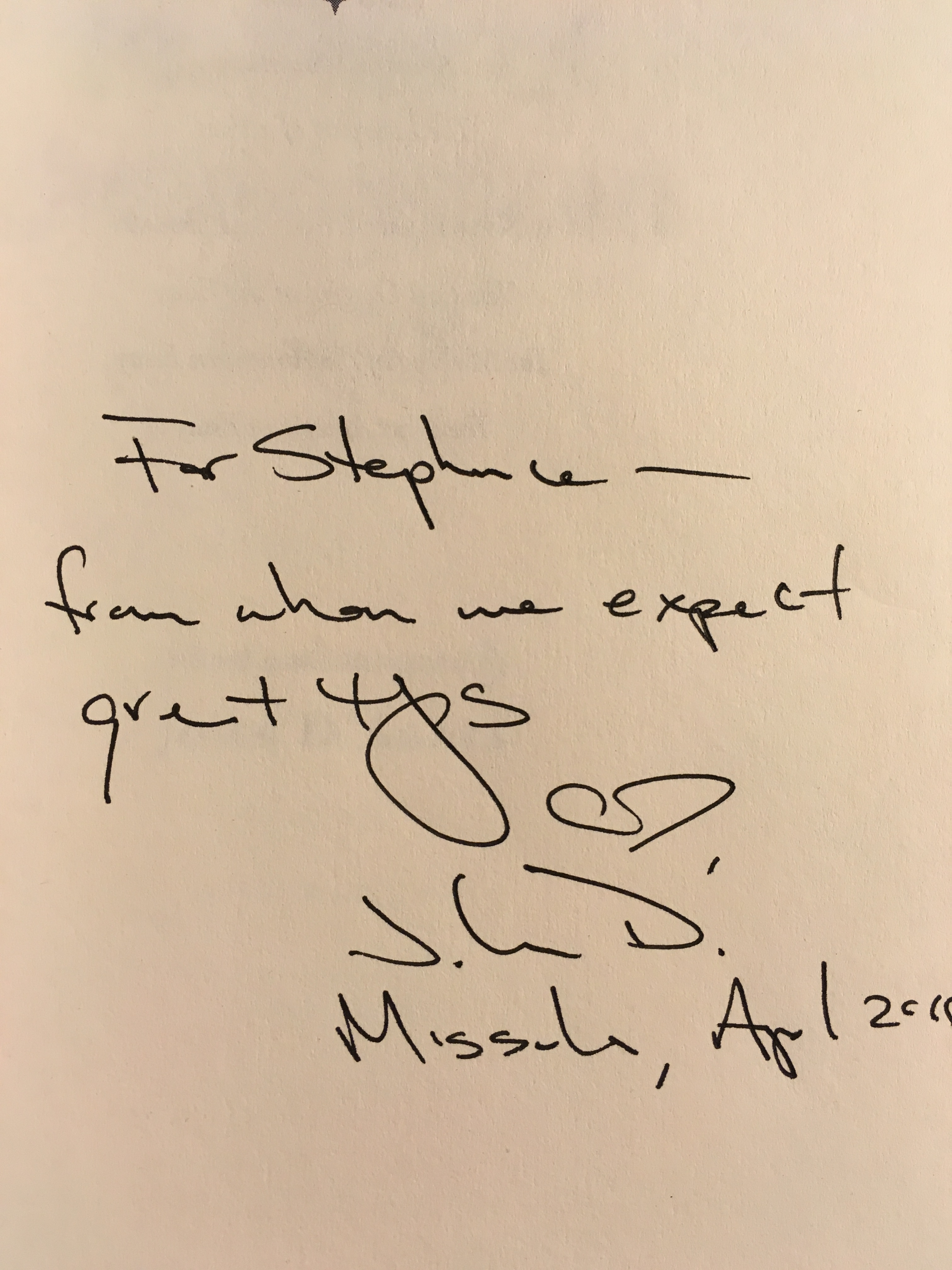

Exactly 11 months after my essay about cleaning houses was published on Vox and went viral, I accepted the offer for my memoir—an expansion of that essay. For months, I’d spent what I felt were luxurious hours not writing for pay, but working, quietly at night, with a sleeping baby in my lap, crafting the perfect book proposal with my agent, Jeff Kleinman at Folio. It felt incredibly strange to be going after something I’d wanted since I was ten years old, and at first, I didn’t have much faith in it. For over twenty years, I had been writing, reading, and studying the art of writing. It was shocking to even have an agent.

Exactly 11 months after my essay about cleaning houses was published on Vox and went viral, I accepted the offer for my memoir—an expansion of that essay. For months, I’d spent what I felt were luxurious hours not writing for pay, but working, quietly at night, with a sleeping baby in my lap, crafting the perfect book proposal with my agent, Jeff Kleinman at Folio. It felt incredibly strange to be going after something I’d wanted since I was ten years old, and at first, I didn’t have much faith in it. For over twenty years, I had been writing, reading, and studying the art of writing. It was shocking to even have an agent. I would work on that essay for the next two years, chiseling away at it little by little. When Vox bought it for $500, I about fell over. It seemed a massive amount of money, especially since I had spent the last eight years on assistance programs, and my current hourly wages from various freelancing jobs were about $10.00. I thought it would surely be the most I’d ever receive for my writing. When the essay went viral, with almost 500,000 hits in the span of three days, my career took off. Within two months, accepted a position as a writing fellow with the Center for Community Change, and had several more pieces published, including one through Barbara Ehrenreich’s Economic Hardship Reporting Project.

I would work on that essay for the next two years, chiseling away at it little by little. When Vox bought it for $500, I about fell over. It seemed a massive amount of money, especially since I had spent the last eight years on assistance programs, and my current hourly wages from various freelancing jobs were about $10.00. I thought it would surely be the most I’d ever receive for my writing. When the essay went viral, with almost 500,000 hits in the span of three days, my career took off. Within two months, accepted a position as a writing fellow with the Center for Community Change, and had several more pieces published, including one through Barbara Ehrenreich’s Economic Hardship Reporting Project. With that,

With that,  A couple of weeks after I accepted the offer, Krishan and I spoke again on the phone. “I just have to tell you,” she said. “Our office, our floor, is all open. When we received the news that you’d accepted our offer, everyone jumped up from their desks to cheer, and started hugging each other. Even the CEO of the company came out to give me a hug. I’ve never seen anything like that in publishing before. It was amazing.”

A couple of weeks after I accepted the offer, Krishan and I spoke again on the phone. “I just have to tell you,” she said. “Our office, our floor, is all open. When we received the news that you’d accepted our offer, everyone jumped up from their desks to cheer, and started hugging each other. Even the CEO of the company came out to give me a hug. I’ve never seen anything like that in publishing before. It was amazing.”

Mornings have been different lately. We all get up together, and if Cora is extra grumpy, Mia and I switch duties. While I am outside, waiting for the dog to sniff out a good spot to pee and poop, Mia is inside, getting Coraline out of her rumpled, just-slept-in-pajamas, changes her diaper, and puts her in an extra-cute outfit for daycare. I hear them laughing and singing as I walk back inside, a sharp contrast to mornings when Mia was in Kindergarten, when

Mornings have been different lately. We all get up together, and if Cora is extra grumpy, Mia and I switch duties. While I am outside, waiting for the dog to sniff out a good spot to pee and poop, Mia is inside, getting Coraline out of her rumpled, just-slept-in-pajamas, changes her diaper, and puts her in an extra-cute outfit for daycare. I hear them laughing and singing as I walk back inside, a sharp contrast to mornings when Mia was in Kindergarten, when

For the next couple of weeks, Coraline started daycare full-time, and I worked a staggering amount. In the week I had the reporter and photographer from the newspaper come interview me, I wrote about 11,000 words. I didn’t think of this as “writing.” This was producing.

For the next couple of weeks, Coraline started daycare full-time, and I worked a staggering amount. In the week I had the reporter and photographer from the newspaper come interview me, I wrote about 11,000 words. I didn’t think of this as “writing.” This was producing.

There is beauty, of course. There are moments of laughter and joy. There are friends who check in, who come over to talk, who invite one or both of my children over to play.

There is beauty, of course. There are moments of laughter and joy. There are friends who check in, who come over to talk, who invite one or both of my children over to play. Being a mother is also something I do very well, but I can’t say it’s my passion. I don’t enjoy playing, or going to parks or story time at the library. Although I am a good mother, it’s not because I mother my children directly all the time. I outsource my mothering duties. As a single mother especially, there’d be no way I could possibly be everything to my children all the time. I’d have nothing left of me. I’d have no career. My life requires a rotating, constant set of characters that step in to replace me for a time, or I would surely dissolve.

Being a mother is also something I do very well, but I can’t say it’s my passion. I don’t enjoy playing, or going to parks or story time at the library. Although I am a good mother, it’s not because I mother my children directly all the time. I outsource my mothering duties. As a single mother especially, there’d be no way I could possibly be everything to my children all the time. I’d have nothing left of me. I’d have no career. My life requires a rotating, constant set of characters that step in to replace me for a time, or I would surely dissolve. I always return to that quote by Joseph Conrad. He focused on the rivets, saying it was the little things that made all the difference. An article published on a platform I’ve pined for, being fully present while my toddler goes down a slide, laughing with a friend: they’re the little moments that keep the ship together, and chugging up the river.

I always return to that quote by Joseph Conrad. He focused on the rivets, saying it was the little things that made all the difference. An article published on a platform I’ve pined for, being fully present while my toddler goes down a slide, laughing with a friend: they’re the little moments that keep the ship together, and chugging up the river. A somewhat precious thing I’ve discovered, despite the sadness involved, is that I knew Whitney before he got sick. I knew him for a short time, over a decade ago, and remember it so clearly because…I’m not sure why exactly. Whitney forced me to see the beauty in myself. He saw only my core. We communicated on a level of raw understanding and deep connection, even though we’d only known each other for a few short weeks. You can chalk it up to whatever you like but in knowing who Whitney is, the words people describe him as are things like magic, and enlightened.

A somewhat precious thing I’ve discovered, despite the sadness involved, is that I knew Whitney before he got sick. I knew him for a short time, over a decade ago, and remember it so clearly because…I’m not sure why exactly. Whitney forced me to see the beauty in myself. He saw only my core. We communicated on a level of raw understanding and deep connection, even though we’d only known each other for a few short weeks. You can chalk it up to whatever you like but in knowing who Whitney is, the words people describe him as are things like magic, and enlightened. Cora’s clothes are on a shelf in my closet. Her socks are in the top drawer of the pink dresser in my room. For daycare, she needs what’s in the black bag in the bin next to the kitchen table. They go outside, so she needs a warm coat and boots.

Cora’s clothes are on a shelf in my closet. Her socks are in the top drawer of the pink dresser in my room. For daycare, she needs what’s in the black bag in the bin next to the kitchen table. They go outside, so she needs a warm coat and boots. Khadijah Queen’s essay on “

Khadijah Queen’s essay on “ I started this blog years ago, before mommy blogs were popular, as a way to pick out pieces of my often lonely days with Mia that I wanted to remember. I needed to do that in order to stay sane, but also to be a present parent for her. If I spent even ten minutes remembering, and writing, later that night when she screamed and fought me over eating or going to bed, I could go back to that place where I meditated on the way her hands looked as she carefully picked up a crab with a yellow plastic shovel.

I started this blog years ago, before mommy blogs were popular, as a way to pick out pieces of my often lonely days with Mia that I wanted to remember. I needed to do that in order to stay sane, but also to be a present parent for her. If I spent even ten minutes remembering, and writing, later that night when she screamed and fought me over eating or going to bed, I could go back to that place where I meditated on the way her hands looked as she carefully picked up a crab with a yellow plastic shovel. Because it’s still just me, sitting alone, at a computer, staring at a wall of photos and grabbing a mug to take a drink of coffee that is long-since gone. I have to remind myself to get up, to eat, to stop staring, and walk around a bit.

Because it’s still just me, sitting alone, at a computer, staring at a wall of photos and grabbing a mug to take a drink of coffee that is long-since gone. I have to remind myself to get up, to eat, to stop staring, and walk around a bit. I looked over at my girls, playing so sweetly together, and thought of when Coraline was just born. I was completely on my own in an empty house just two days after I’d given birth. My cousin had stayed with us for a few days, and left us with a freezer full of pasta dishes, and some friends had brought us some food. Other than that, I was alone with a newborn who screamed if I put her down, and a rambunctious 7-year-old who, though I didn’t know it at the time, had hair completely full of lice.

I looked over at my girls, playing so sweetly together, and thought of when Coraline was just born. I was completely on my own in an empty house just two days after I’d given birth. My cousin had stayed with us for a few days, and left us with a freezer full of pasta dishes, and some friends had brought us some food. Other than that, I was alone with a newborn who screamed if I put her down, and a rambunctious 7-year-old who, though I didn’t know it at the time, had hair completely full of lice. Despite all of this, I’ve already been published several times this year, and am putting the finishing touches on a book proposal that I hope to send out in the next week.

Despite all of this, I’ve already been published several times this year, and am putting the finishing touches on a book proposal that I hope to send out in the next week.