In Going to Visit a Friend Who’s Sick

I told someone about the time Whitney and I had together recently, and said it was the perfect summer romance.

I told someone about the time Whitney and I had together recently, and said it was the perfect summer romance.

“We had a month. Exactly a month. And he was leaving and we’d never see each other again,” I said. “So we had this month of intense connection without worrying about whether or not it’d turn into a relationship. We could just be with each other, and love each other as much as we wanted without any stress over the future.”

*

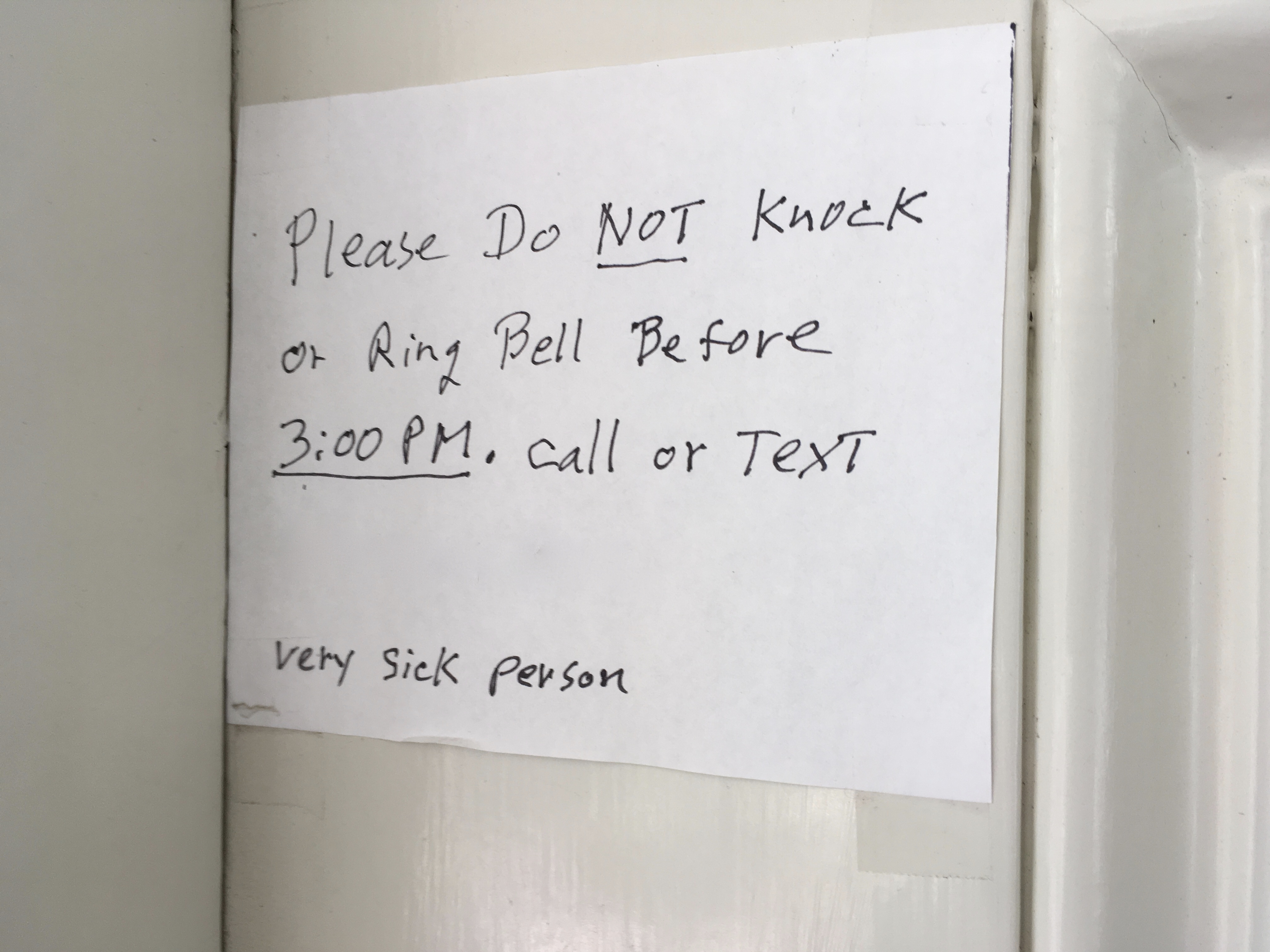

In going to visit a friend who’s sick, and telling people I’m doing so, most of the reactions are sad moans and frowns. When I said I wouldn’t be able to see him, they’d cock their head to the side a little and furrow their brows in confusion.

“He can’t tolerate anyone being in his room,” I tried to explain. “He’s too sick. He’ll crash if his brain is forced to process who I am and why I’m there and he’d go into a vegetative state. His body would shut down.”

“He can’t tolerate anyone being in his room,” I tried to explain. “He’s too sick. He’ll crash if his brain is forced to process who I am and why I’m there and he’d go into a vegetative state. His body would shut down.”

“But I thought he only had chronic fatigue syndrome?”

I barely understood the science of it, or how it worked. The only way I could think of explaining it was that, even though he’d spent most of his time lying in bed for the last three years, it was more like he’d been resting with his eyes closed.

I barely understood the science of it, or how it worked. The only way I could think of explaining it was that, even though he’d spent most of his time lying in bed for the last three years, it was more like he’d been resting with his eyes closed.

“Imagine how you’d feel if you hadn’t had any restorative type of sleep in three years. His entire body is so exhausted, any amount of energy output shuts him down to a hibernation-type of state.”

“From chronic fatigue syndrome?”

And so it goes. I can’t imagine what it’s like for patients to explain their daily lives to friends and family or doctors.

*

It was late at night when I pulled into the driveway of the house where Whitney grew up. Even though his parents, Janet and Ron, had left the door unlocked for me, I still felt like a stranger creeping into the house. It’d been over 13 years since I’d seen Whitney, 10 or 11 since we’d talked on the phone, and over a year since I’d received any kind of message from him.

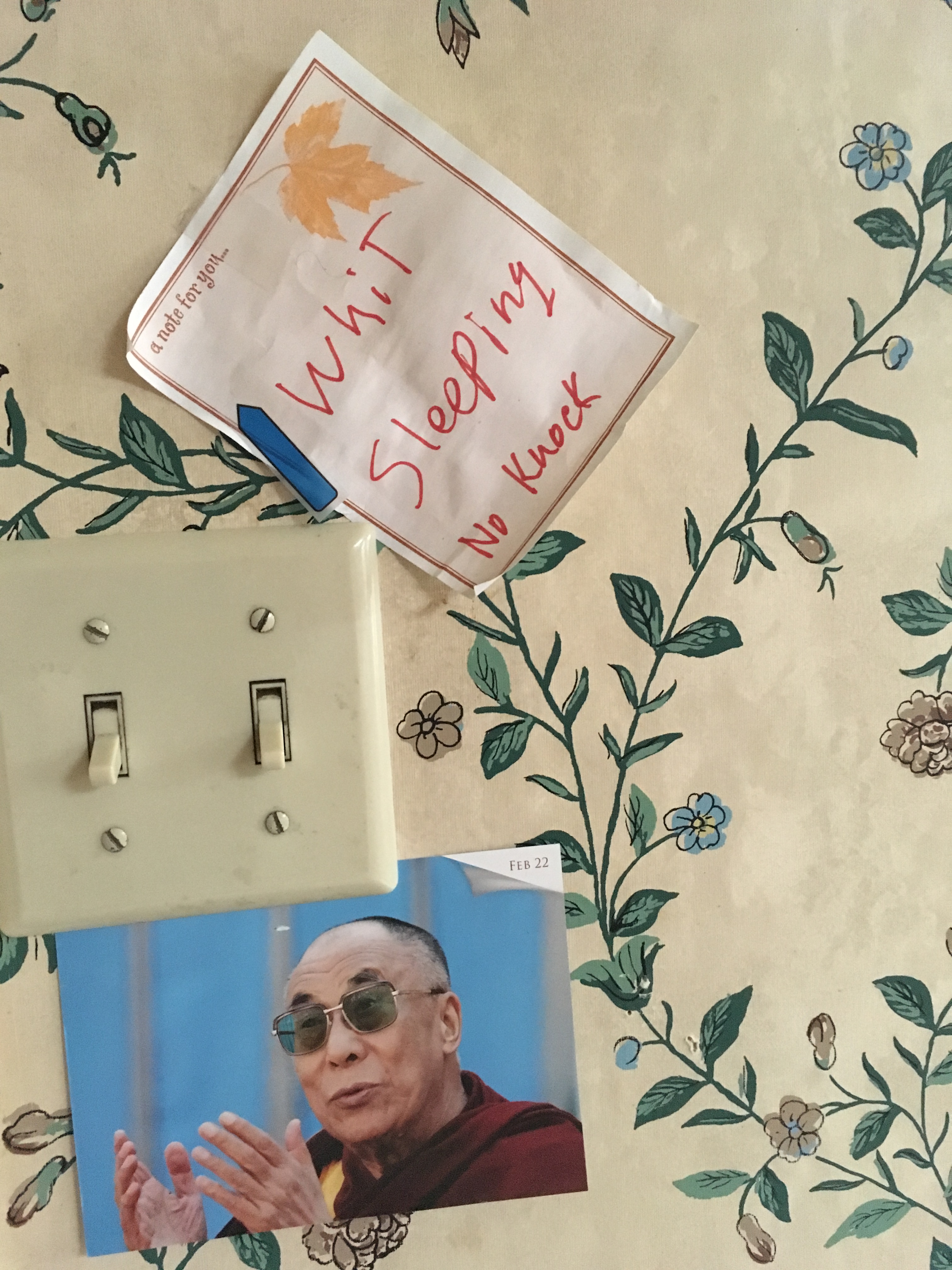

Ron and Janet’s nightly routine consists of quietly shuffling in and out of the back room where Whitney lives. The room he never leaves. He has to be prepared for them to enter the room, has to know when to expect them. Once inside, they work quickly to meet his needs then leave him be. On my first night at the house, I watched all of this with a mix of awe and helplessness.

When I finally went to sleep in the living room, I could still hear Janet moving around in the kitchen. Sometimes she’s still awake when Whitney’s sister, Ashley, gets up for work in the morning.

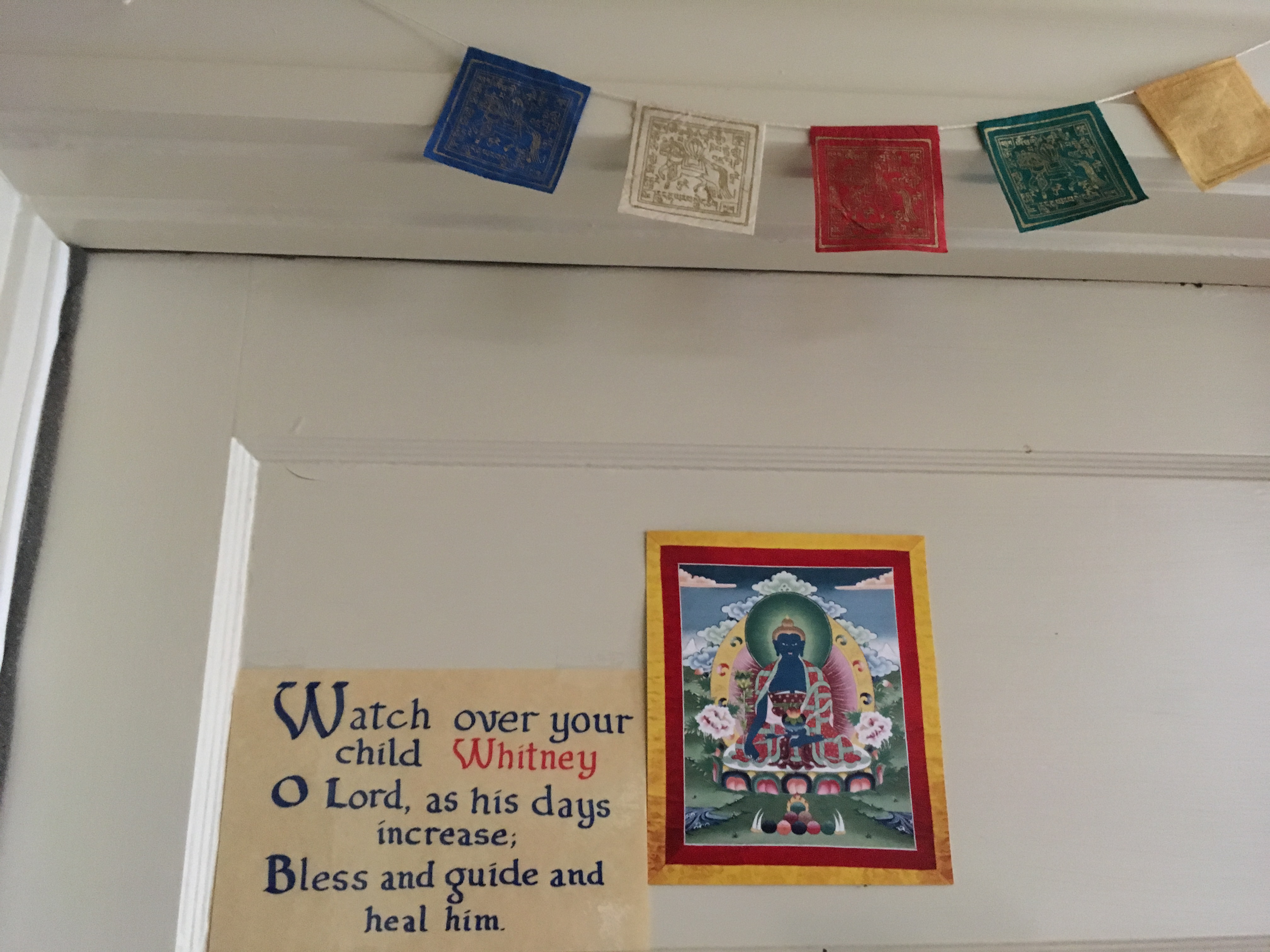

Tibetan prayer flags hang over Whitney’s door, above the porch, and all over the back stoop leading from Whitney’s room. When Janet took me out back to look at the forget-me-nots and African daisies Whitney had planted, she said he might be able to see me from the window. I got nervous and hopeful at the same time. I tried not to look in the direction of his room, but after a while I couldn’t help it. He’d planted my favorite flowers all over the yard, and they, along with the columbine he’d planted for his mom, were some of the only ones in bloom. In the backyard, Janet and I talked in whispers. I caught myself staring at the the back bedroom, at the walls that encased him. At the house that keeps him safe, living with the disease that imprisons him.

Late that night, Janet, Ron and I sat on couches in front of their television, watching the old film East of Eden. Janet had to go back to caring for Whitney, and Ron had to get to bed. I stayed up, finished the movie, and waited to see if Janet would come back anytime soon.

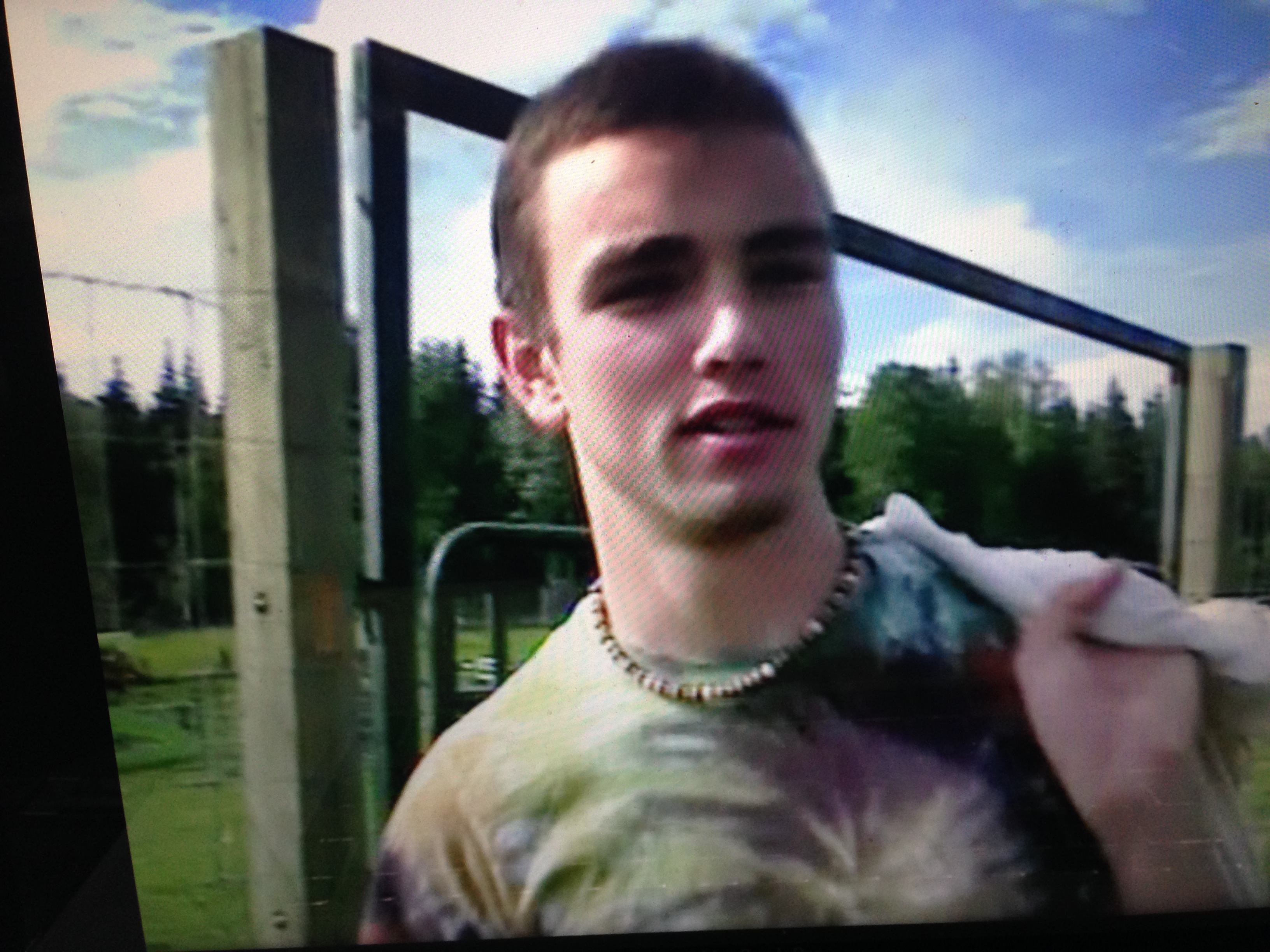

Whitney Dafoe on Feb. 20, 2016. Courtesy of Janet Dafoe.

Around midnight, she came walking back into the room, a look of disbelief on her face. “Oh my god!” She said, and sat down on the couch next to me. “He asked for food in his j-tube!”

Janet explained that exactly three months ago, Whitney had undergone surgery to insert a feeding tube leading directly into his small intestine. Though the tube was designed to inject a special concoction of nutrients, he had only received water so far. Anything else was too painful. But that night, just after the last scene in East of Eden, Whitney had, for the first time, pantomimed to Janet that he wanted the nutrient mixture.

Before going to California, I wasn’t sure that showing up as a houseguest was a good idea. I felt like I was putting out a family already so overburdened with all of the tasks involved in monitoring and caring for their severely ill son. But Ron said “it’s good to have you here,” and I believed him.

Before I left, I walked around the house and took some pictures. I tried to capture the present and the past—anything that reminded me of Whitney, anything with his handwriting, or photos of him displayed around the house. I took a picture of a spice jar containing turmeric that Whitney had labeled as his. I could have sworn he’d brought the same jar to Alaska when I met him a decade ago.

*

An avid photographer, Whitney had taken hundreds of photos of us in Alaska—feeding caribou, sitting in a field with muskoxen, journaling and doing art side by side. For me, that time exists only in memories and a couple of letters Whitney had written to me after we parted ways. But any photographs I had are now long gone.

The day after I returned home to Montana, Janet called me. I could hear the excitement in her voice. She explained she’d asked someone to convert all of her home movies to DVDs. After finding a video that Whitney had taken in Alaska, he called Janet. “There was this girl that he had obvious chemistry with,” he told her.

I was stunned. I had no recollection of him using a video camera.

A few days later, at two in the morning, Janet sent me a text. “It’s you in the video.”

I got out of bed and tiptoed out to the living room, trying not to wake my two sleeping daughters. We Skyped and Janet pointed her laptop towards the television so I could watch the video with her. It was almost like we were sitting next to each other again—instead of East of Eden, it was me on the screen. I had blonde streaks in my hair, and looked plump and shorter somehow. Then I remembered how tall Whitney is—over 6 feet—and realized that the video would have been taken from his height.

The footage is a little grainy, and the light is dusk. We are standing next to the caribou pen. I am wearing his college sweatshirt, and Whitney is interviewing me. He mentions that it’s near midnight. When he speaks in the video, there is a fluttering of memory and love and grief in my chest. I’d forgotten how deep his voice was.

The footage is a little grainy, and the light is dusk. We are standing next to the caribou pen. I am wearing his college sweatshirt, and Whitney is interviewing me. He mentions that it’s near midnight. When he speaks in the video, there is a fluttering of memory and love and grief in my chest. I’d forgotten how deep his voice was.

“I think this was the night before he left Alaska,” I said to Janet, as we Skyped together. It was a little like putting a puzzle together, trying to figure out when the video had been taken. “If we’d already traded sweatshirts, then he was about to leave.”

I watched with heartache. “Stephanie Land,” Whitney said a few times when he would put the camera on me. Once I caught him doing a close-up of my face from a way’s away and I turned to smile at him. Then I puckered up my lips, sending a kiss in his direction.

All video stills provided by Janet Dafoe.

The home movie stopped for a second, then started again. In the next frame, it was sunny. The camera was pointed in my direction. I stood behind my Subaru in a t-shirt that I’d coincidentally worn at his house that week. The hatch was open, raised above my head. This memory is hazy, but is still somewhere in my brain. As I watched the video, the memory became clearer. It was the morning before he left. I remember trying to keep the emotion from bubbling up inside of me. In the video, it is clear that I’m trying my hardest to not let the sadness show on my face. I didn’t want him to leave.

Then, blurriness, as Whitney turned the camera around to his face.

From my living room in Montana, I sucked in a breath. I remember doing the same thing when I was with him in Alaska—how sometimes he would cause me to lose my breath. Janet commented on how young he looked. He was only 19.

In the video, he gives me the camera and I follow him into the caribou pen at the Large Animal Research Station, where he’d been working as a photographer all summer. I left the camera focused on him while he knelt down, and fed a small group of caribou some mossy snacks.

In the video, he gives me the camera and I follow him into the caribou pen at the Large Animal Research Station, where he’d been working as a photographer all summer. I left the camera focused on him while he knelt down, and fed a small group of caribou some mossy snacks.

Other than the surroundings and the act of hand-feeding caribou, there wasn’t anything particularly special in what Whitney was doing. But the video made me remember what it was like to be so close to him, to be able to touch him, each of us a satellite to the other’s moon, a couple of kids caught up in a summer romance for a few weeks.

In the caribou pen, he put his face close to some yearlings, nearly touching their noses with his lips. The video ended with him holding the camera as he lay back in the grass, several caribou sniffing at him, hoping for more treats.

In the caribou pen, he put his face close to some yearlings, nearly touching their noses with his lips. The video ended with him holding the camera as he lay back in the grass, several caribou sniffing at him, hoping for more treats.

Earlier in the video, he’d asked his roommate if she thought he loved me. She had nodded yes. At least I thought so, anyway, when I watched it—I couldn’t hear it very well. I know I heard him say the words “I love her,” and that’s all that matters.

When we were in Alaska, I didn’t think I’d really made much of an impact in his life. I didn’t think he felt all that much for me. But seeing him watch me through the lens of a video camera, I know now how foolish I was to assume that.

When I talk to Janet, I always tell her to send Whitney my love however she can. I can’t wait until the day I’m able to do it myself.

Donate to help find a cure for Whitney, and an estimated 2.5 million who suffer in silence HERE.

-step.