Sometimes You Go To California

On Tuesday night of this week I stood at a podium in front of a class of about 40 students. In my hands I held out a printed copy of the essay I’d recently had published through the Longreads blog about Whitney Dafoe. It wouldn’t be the first time I’d read it out loud. I’d practiced over a dozen times in the previous few weeks. My voice shook, even when I was alone in my apartment, and sometimes my eyes stung and watered.

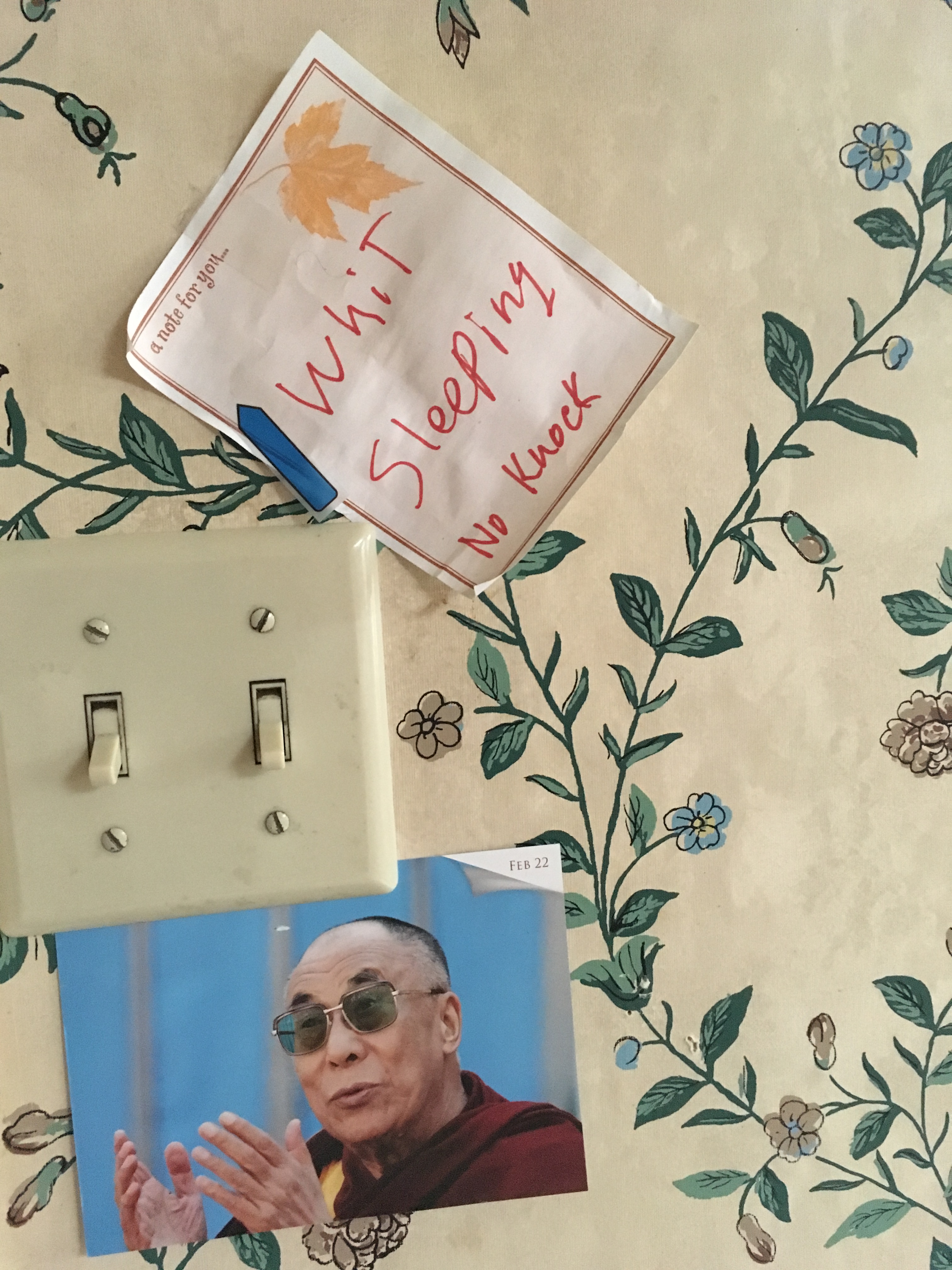

“This piece is really raw for me right now,” I said. I didn’t say why, and instead started to read. I would have to explain that I’d been at Whitney’s house the day before. That I saw in a book a photo I’d taken in Alaska of him standing on his work truck to take a picture. That over the weekend, I’d seen his mother burst into tears over hearing the lyrics of a song. And through it all had known, once again, that he had no idea I was there. I’m sure I would have lost my composure halfway through.

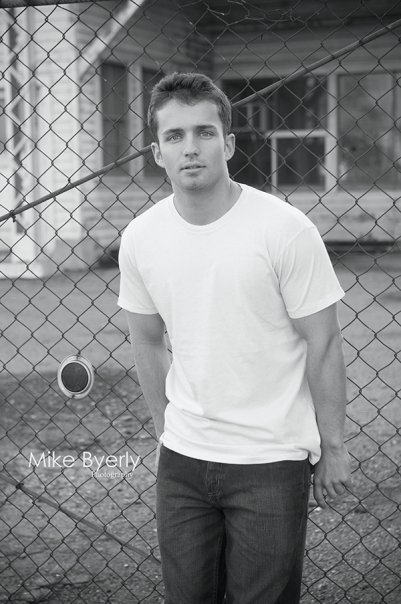

Photo courtesy of the Davis-Dafoe family.

Every time I looked up, I saw blank faces, mouths agape, and one student was audibly crying. I felt horrible, but owned my decision to read the essay. I force ME/CFS in people’s faces so that, someday, it won’t be a depressing conversation.

I’d gained a new person to carry constantly in my pocket that weekend. Jamison Hill and I had been friends through email and text for several months, and a large part of my trip to California was the chance to meet him in person.

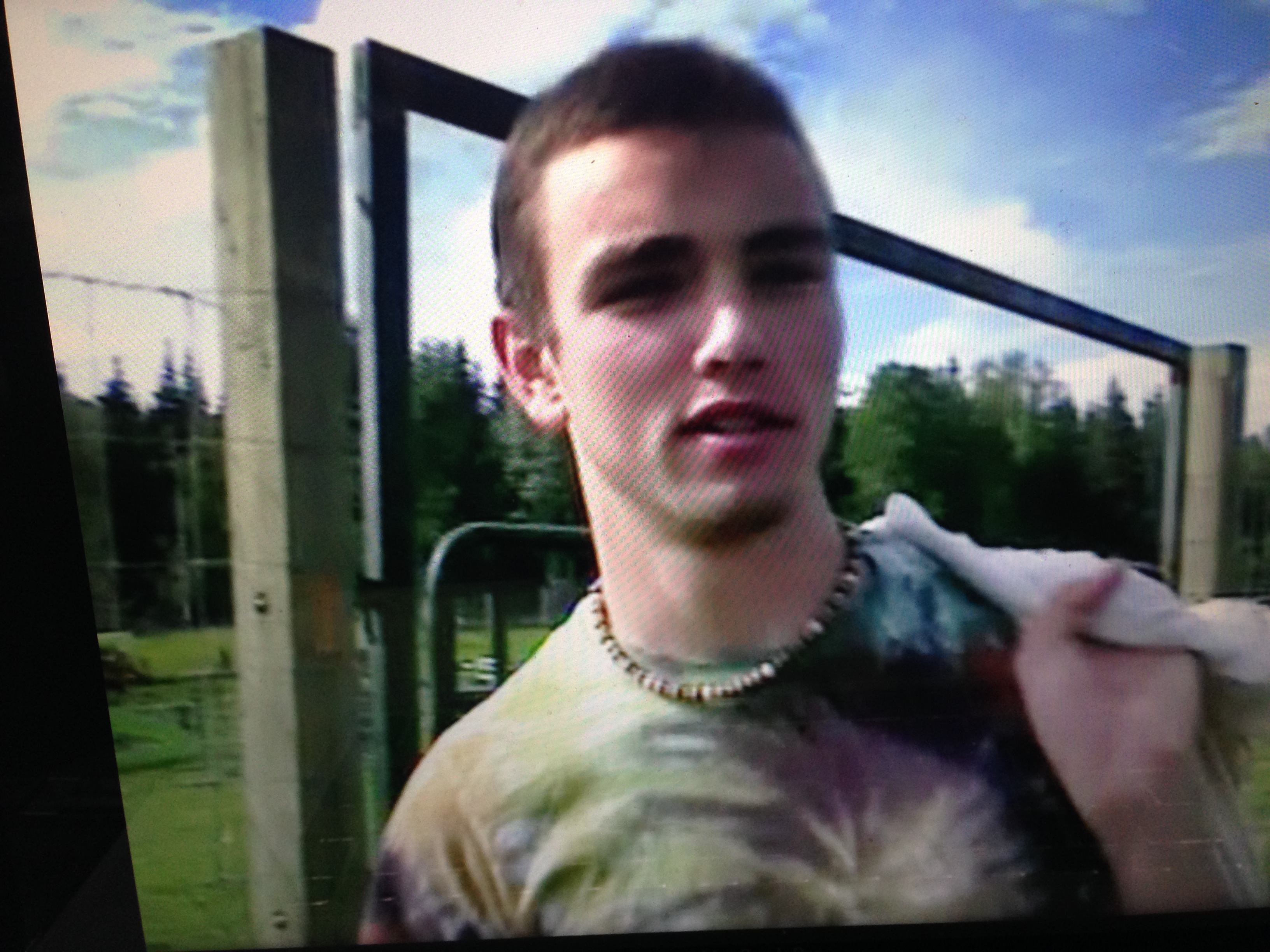

Photo courtesy of Jamison Hill

Jamison, for those who are unfamiliar, was featured in my friend Ryan Prior’s Forgotten Plague along with Whitney. Jamison’s the one in the documentary’s trailer who’s laughing, his dimples going deep into his cheeks, his bright blue eyes shining despite being one of the millions missing from ME/CFS. It’s been six years since, right around Thanksgiving, that Jamison went to the gym early in the morning like he always did, and couldn’t finish a workout he normally did thoughtlessly. His story is one of the terrifying ones: he went from being a physical trainer, a model, an amateur body builder, and otherwise active 22-year-old college student to in bed, sick, getting rapidly worse in a matter of years.

Before Jamison submitted a story for me to publish at the Blue Ribbon Foundation’s “Share your Story” section, I’d only heard that he’d become as bad as Whitney. I’d seen GoFundMe fundraisers to help with housing, medical expenses, and treatment. When Ryan spoke of him, his voice grew soft; a tone I’d come to recognize in the ME/CFS community as a person who’d taken a turn for the worse. A person who was living a form of death.

Jamison later explained that he’d been in a cave for the last 18 months, unable to tolerate daylight, clothing, speaking, or chewing. Coming out of it through saline IV treatments was a rebirth. Even though he had a chance at a new life, he was still unable to sit up in bed. But he could make sounds that people understood. He could eat food. He could communicate with people through email and text.

Jamison later explained that he’d been in a cave for the last 18 months, unable to tolerate daylight, clothing, speaking, or chewing. Coming out of it through saline IV treatments was a rebirth. Even though he had a chance at a new life, he was still unable to sit up in bed. But he could make sounds that people understood. He could eat food. He could communicate with people through email and text.

I knew most of this through reading a lot of what he’d written, but to see it was something else entirely. Ashley, Whitney’s sister, drove me, my daughter Mia, and Janet, Whitney’s mom, to Jamison’s house three hours east. We arrived at sunset, enamored with the view from the porch. Janet was the first one to go in and visit with Jamison. I was the second.

Before going back to his room, I was worried what germs I might have on my clothes. A simple cold virus could knock him down further. I was worried seeing me would cause him to crash. But mainly I was worried that he’d go beyond his limits and wake up the next morning feeling horrible and unable to move.

When I read what Jamison wrote about meeting me in his blog, what stuck out the most was that he’d hoped seeing him, smiling and sitting up would give us, his largest group of visitors in years, a new hope for Whitney.

But Jamison’s just like that. He’s easily one of the happiest, lovable humans I know. In the months of us emailing and texting back and forth, he’s gone into frustrated rants maybe twice. And a few times I had to specifically ask for them. Seeing him, sitting there, knowing he hadn’t gotten out of bed in almost two years, I was completely in awe of his ability to maintain any semblance of who he’d been six years earlier.

So we smiled at each other. I hugged him a bunch, and held his hand. We made jokes, told a few dating horror stories, and then it was time for me to give him a break.

So we smiled at each other. I hugged him a bunch, and held his hand. We made jokes, told a few dating horror stories, and then it was time for me to give him a break.

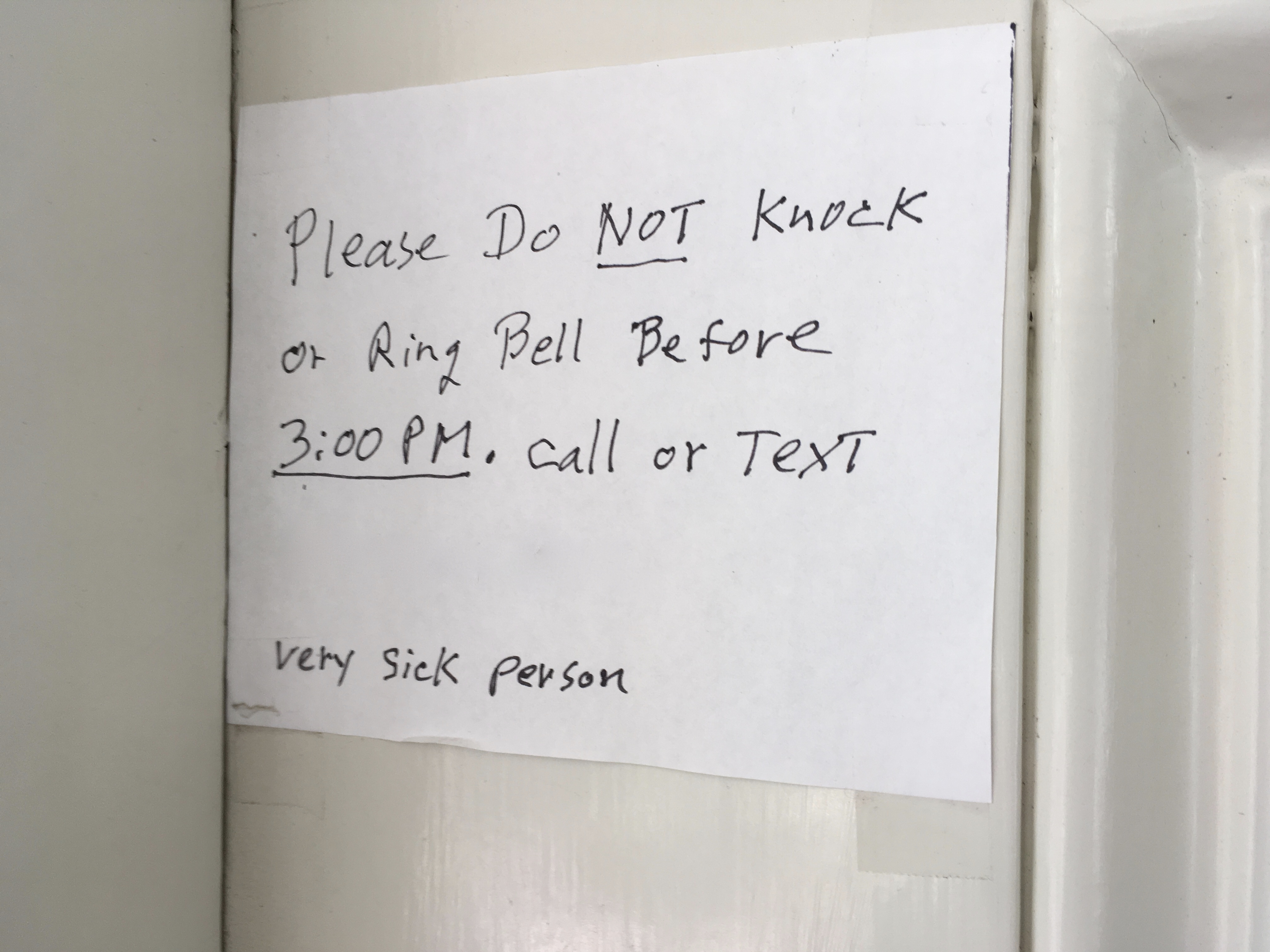

We texted late into the night. I kept asking him the next day if he felt all right. He said yes, and said he wanted to see us again. So I bought him some tea from his favorite little shop, and some fudge. We drove up to his house at sunset again, and took some pictures on the porch. I went inside to use the bathroom, and snuck across the hall to Jamison’s room.

He had thick blankets on the windows and the lights off. I couldn’t see anything, then saw the faint light of the screen of his phone–his signal to tell me where he was. I saw his shape then. He wasn’t sitting up. He was on his left side, bent over almost in a fetal position, his cheek pressed against the bed. Crashed.

I felt his hand reach out for mine and sank to my knees at the same time. My other arm went around his back, my right cheek on his head. He only had boxers on with a sheet covering his legs and feet. His mom came in to open the curtains all the way so we could see each other. I stayed that way for a bit, whispering that he should have told me he had what ME/CFS patients call “the world’s worst hangover.”

He wanted to know how long we were staying, and where we were going next, and, of course, offered ideas of where to go eat dinner. He couldn’t talk like he did the day before. Most of this I either figured out through pantomime or he had to type out on his phone.

I went in the second time after everyone else had visited to kneel down by his bed to say goodbye. He held my hand tighter, and whispered “I’m so tired of this shit.” I told him I think about him constantly. That I love him. And that I’d miss him dearly. That I’d be back to visit as soon as I could to be there more than just an hour or two. “I’ll spoon you next time,” I said, and he chuckled.

I stood out in the living room, watching Janet hug Jamison’s mom, Kathleen. “We have amazing sons,” Janet said. They were crying. A stark contrast to the night before, when we’d been celebrating recovery. Kathleen went in to check on Jamison and he wanted us all to come back, stand in the hallway, and wave goodbye one more time.

“He just wants to see your faces again,” his mom said. So we stood there, blowing kisses, waving, watching him do it in return from his dark room. The cave. For the next day, as I told him I was on my way to the airport he’d text “Damn. Don’t go.”

“He just wants to see your faces again,” his mom said. So we stood there, blowing kisses, waving, watching him do it in return from his dark room. The cave. For the next day, as I told him I was on my way to the airport he’d text “Damn. Don’t go.”

From the moment I’d left the hallway of his room I hadn’t wanted to. I didn’t want to drive away from Whitney’s house, watching Janet and Ron wave goodbye. It’s a different sort of grief, to feel too helpless, too far away, and isolated.

After I read the essay the next night, one of the students asked me if I had any advice on writing. I told them what everyone says: to sit in a chair and motherfucking write. But the next day Jamison reminded me of the necessary part that needs to exist before that.

“There is only one thing you should do,” Rilke wrote. “Go into yourself. …confess to yourself whether you would have to die if you were forbidden to write. This most of all: ask yourself in the most silent hour of your night: must I write? …if you meet this solemn question with a strong, simple ‘I must,’ then build your life in accordance with this necessity…”

Jamison writes everything on his phone. He can’t use a laptop, can’t stand looking at the screen. He wrote the last bit of his book looking at his phone through tanning goggles. That amount of passion, that desire to write words, humbles me. Even though I am finishing this post in the chaos of bedtime with a two-year-old on the floor tearing apart paper and throwing markers, it would take a crazy amount of passion for me to write this out on my phone. I’ve written in journals since I was 10 years old, and I deeply admire Jamison’s amount of “must” to write. To live.

step.

I walked around the United States capitol with Ryan for a few hours before the protest. It was hotter than I thought it’d be, and sweat dripped down my back into the waistband of my jeans. Ryan had changed into a dark shirt before we left, and he fought to keep the sleeves rolled above his elbows. I kept looking for signs he’d had enough. But ever the tour guide, he showed me the town he loved, walking me to the Library of Congress, and through the stuffy viewing platform. We paused to buy food and sat to eat it on a shady bench. We walked down past the Smithsonian, the Washington Memorial, gazed at the Whitehouse from outside the fence with the cops behind us yelling at tourists to behave. We stopped for souvenirs before sitting on the cool floor in the corner of the Lincoln Memorial. I remembered how the statue had been like a giant when I saw him at seven. How I’d looked up so far the back of my head touched my shoulders a little. Now I understood the weight of the words behind him.

I walked around the United States capitol with Ryan for a few hours before the protest. It was hotter than I thought it’d be, and sweat dripped down my back into the waistband of my jeans. Ryan had changed into a dark shirt before we left, and he fought to keep the sleeves rolled above his elbows. I kept looking for signs he’d had enough. But ever the tour guide, he showed me the town he loved, walking me to the Library of Congress, and through the stuffy viewing platform. We paused to buy food and sat to eat it on a shady bench. We walked down past the Smithsonian, the Washington Memorial, gazed at the Whitehouse from outside the fence with the cops behind us yelling at tourists to behave. We stopped for souvenirs before sitting on the cool floor in the corner of the Lincoln Memorial. I remembered how the statue had been like a giant when I saw him at seven. How I’d looked up so far the back of my head touched my shoulders a little. Now I understood the weight of the words behind him.

I told someone about the time Whitney and I had together recently, and said it was the perfect summer romance.

I told someone about the time Whitney and I had together recently, and said it was the perfect summer romance. “He can’t tolerate anyone being in his room,” I tried to explain. “He’s too sick. He’ll crash if his brain is forced to process who I am and why I’m there and he’d go into a vegetative state. His body would shut down.”

“He can’t tolerate anyone being in his room,” I tried to explain. “He’s too sick. He’ll crash if his brain is forced to process who I am and why I’m there and he’d go into a vegetative state. His body would shut down.” I barely understood the science of it, or how it worked. The only way I could think of explaining it was that, even though he’d spent most of his time lying in bed for the last three years, it was more like he’d been resting with his eyes closed.

I barely understood the science of it, or how it worked. The only way I could think of explaining it was that, even though he’d spent most of his time lying in bed for the last three years, it was more like he’d been resting with his eyes closed.

The footage is a little grainy, and the light is dusk. We are standing next to the caribou pen. I am wearing his college sweatshirt, and Whitney is interviewing me. He mentions that it’s near midnight. When he speaks in the video, there is a fluttering of memory and love and grief in my chest. I’d forgotten how deep his voice was.

The footage is a little grainy, and the light is dusk. We are standing next to the caribou pen. I am wearing his college sweatshirt, and Whitney is interviewing me. He mentions that it’s near midnight. When he speaks in the video, there is a fluttering of memory and love and grief in my chest. I’d forgotten how deep his voice was.

In the video, he gives me the camera and I follow him into the caribou pen at the Large Animal Research Station, where he’d been working as a photographer all summer. I left the camera focused on him while he knelt down, and fed a small group of caribou some mossy snacks.

In the video, he gives me the camera and I follow him into the caribou pen at the Large Animal Research Station, where he’d been working as a photographer all summer. I left the camera focused on him while he knelt down, and fed a small group of caribou some mossy snacks. In the caribou pen, he put his face close to some yearlings, nearly touching their noses with his lips. The video ended with him holding the camera as he lay back in the grass, several caribou sniffing at him, hoping for more treats.

In the caribou pen, he put his face close to some yearlings, nearly touching their noses with his lips. The video ended with him holding the camera as he lay back in the grass, several caribou sniffing at him, hoping for more treats.