On Working

“No, I don’t like work. I had rather laze about and think of all the fine things that can be done. I don’t like work – no man does – but I like what is in the work, – the chance to find yourself. Your own reality – for yourself, not for others – what no other man can ever know. They can only see the mere show, and never can tell what it really means.”

― Joseph Conrad, Heart of Darkness

I’ve been thinking a lot lately about the work that I do. For a long time, I never felt like I did enough. I thought “work” didn’t count unless I logged in specific hours for pay. I didn’t think domestic work counted. I didn’t think doing dishes, laundry, shopping for and preparing food to feed my children (and myself, for that matter) and even playing with my kids counted as work.

The last few days especially have been a fog of fatigue, of exhaustion that causes my eyes to close if I sit down for too long. On days I have my children home with me from when I wake up to when I finally tell myself to go to sleep, I spend every waking minute caring for the two other people (and furry beast) in my home. I eat, hunched over the kitchen counter, in between gulping down coffee or sometimes water and in the evening a blessed glass of wine or beer. I often do not shower. It’s a constant, grueling mess of two children tugging at my legs or mind or emotions.

In between all of this, I fight to work at my job. I email editors pitches in between flipping pancakes. I keep up on the social media side of being a published writer. I field phone calls and texts and emails about different groups and organizations I’m involved in. I have conference calls while the toddler takes things out of the fridge and spills it all over the floor, much to the delight of the dog. I struggle to put pants on her kicking legs, and sometimes start screaming and flailing myself before walking into my bedroom, embarrassed and angry, heart pounding, and wanting to sob.

There is beauty, of course. There are moments of laughter and joy. There are friends who check in, who come over to talk, who invite one or both of my children over to play.

There is beauty, of course. There are moments of laughter and joy. There are friends who check in, who come over to talk, who invite one or both of my children over to play.

But I can’t get away from this overwhelming desire, a primal need to just sit down and write. I’m caught up in freelancing to the point where I could probably write all of my waking hours and still not feel like I’m caught up.

This does not coincide with the work I do at home at all. It is not a gentle give and take. It is an inner battle of fighting to love what I hold most dear.

I love writing. I love that I’ve chiseled out a career where I am a writer by trade who is paid well for it. It’s living a dream. Being a mother, well, I can’t say that has been something I’ve dreamed of being since I was in elementary school. Writing was my first love. It is how I identify myself. It is what I will do until I can’t any longer.

Being a mother is also something I do very well, but I can’t say it’s my passion. I don’t enjoy playing, or going to parks or story time at the library. Although I am a good mother, it’s not because I mother my children directly all the time. I outsource my mothering duties. As a single mother especially, there’d be no way I could possibly be everything to my children all the time. I’d have nothing left of me. I’d have no career. My life requires a rotating, constant set of characters that step in to replace me for a time, or I would surely dissolve.

Being a mother is also something I do very well, but I can’t say it’s my passion. I don’t enjoy playing, or going to parks or story time at the library. Although I am a good mother, it’s not because I mother my children directly all the time. I outsource my mothering duties. As a single mother especially, there’d be no way I could possibly be everything to my children all the time. I’d have nothing left of me. I’d have no career. My life requires a rotating, constant set of characters that step in to replace me for a time, or I would surely dissolve.

Coraline starts daycare full-time next week. Up until this point, it’s been a hodgepodge conglomeration of a couple of daycare days, a babysitter, family, and friends who all pitch in to give me precious hours to work. I started freelancing in earnest a year ago, and have finally reached the point where I easily log in 50-60 hours a week of writing, researching, interviewing, or keeping up on administrative duties. Then I wash, I cook, and I love on my kids until I am falling asleep sitting up on the couch. Having a full 40 hours a week to focus on work, whether it’s direct or domestic, will be huge for me. I hope to shower, and maybe get back into climbing and hiking. I hope to start cooking again, instead of dragging myself to the store and picking up whatever is easiest.

I always return to that quote by Joseph Conrad. He focused on the rivets, saying it was the little things that made all the difference. An article published on a platform I’ve pined for, being fully present while my toddler goes down a slide, laughing with a friend: they’re the little moments that keep the ship together, and chugging up the river.

I always return to that quote by Joseph Conrad. He focused on the rivets, saying it was the little things that made all the difference. An article published on a platform I’ve pined for, being fully present while my toddler goes down a slide, laughing with a friend: they’re the little moments that keep the ship together, and chugging up the river.

I’ve worked two or three jobs for most of my adult life. I am a person who enjoys working, and gets a little nutty if I have too much downtime. Judging from my family history, it’s in my genes. But in these days of feeling so entirely wiped out, I start to wonder if I’ve pushed myself too far, while still getting caught up in the rush that is pitching and getting published. It’s necessary to celebrate the rivets. They keep us together. They keep us moving forward. They are so small, yet vital. They are what holds our life together.

-step.

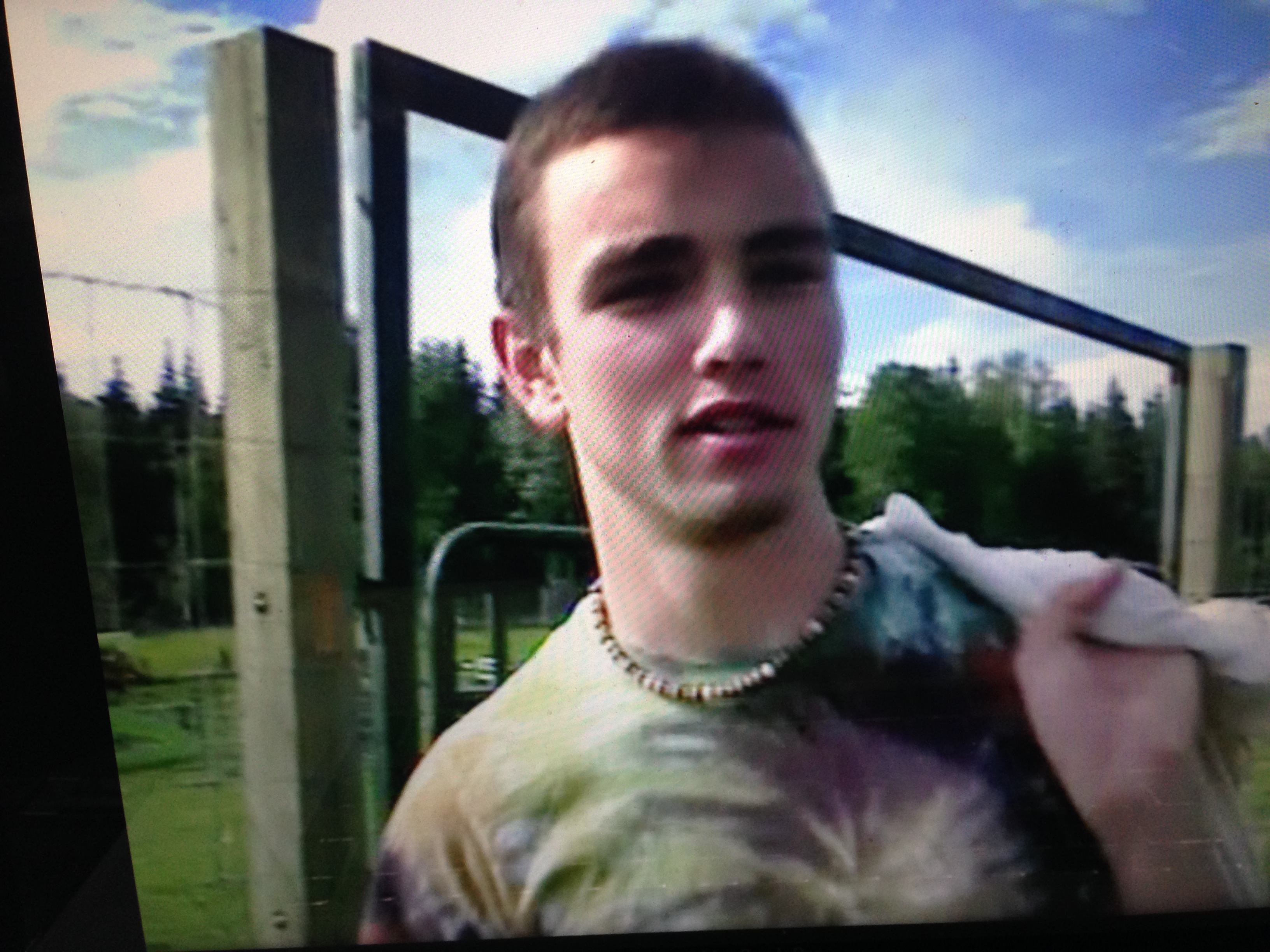

I told someone about the time Whitney and I had together recently, and said it was the perfect summer romance.

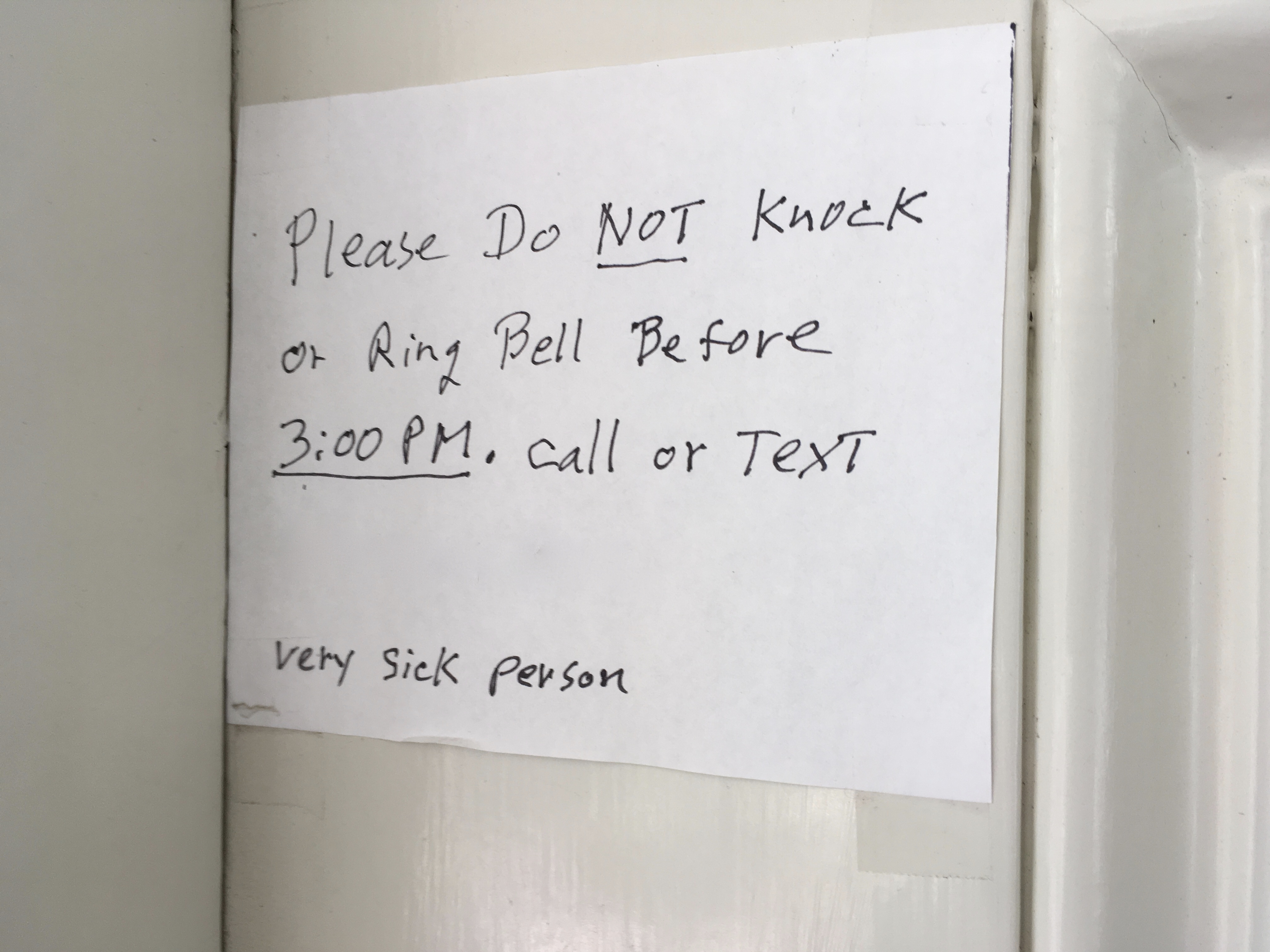

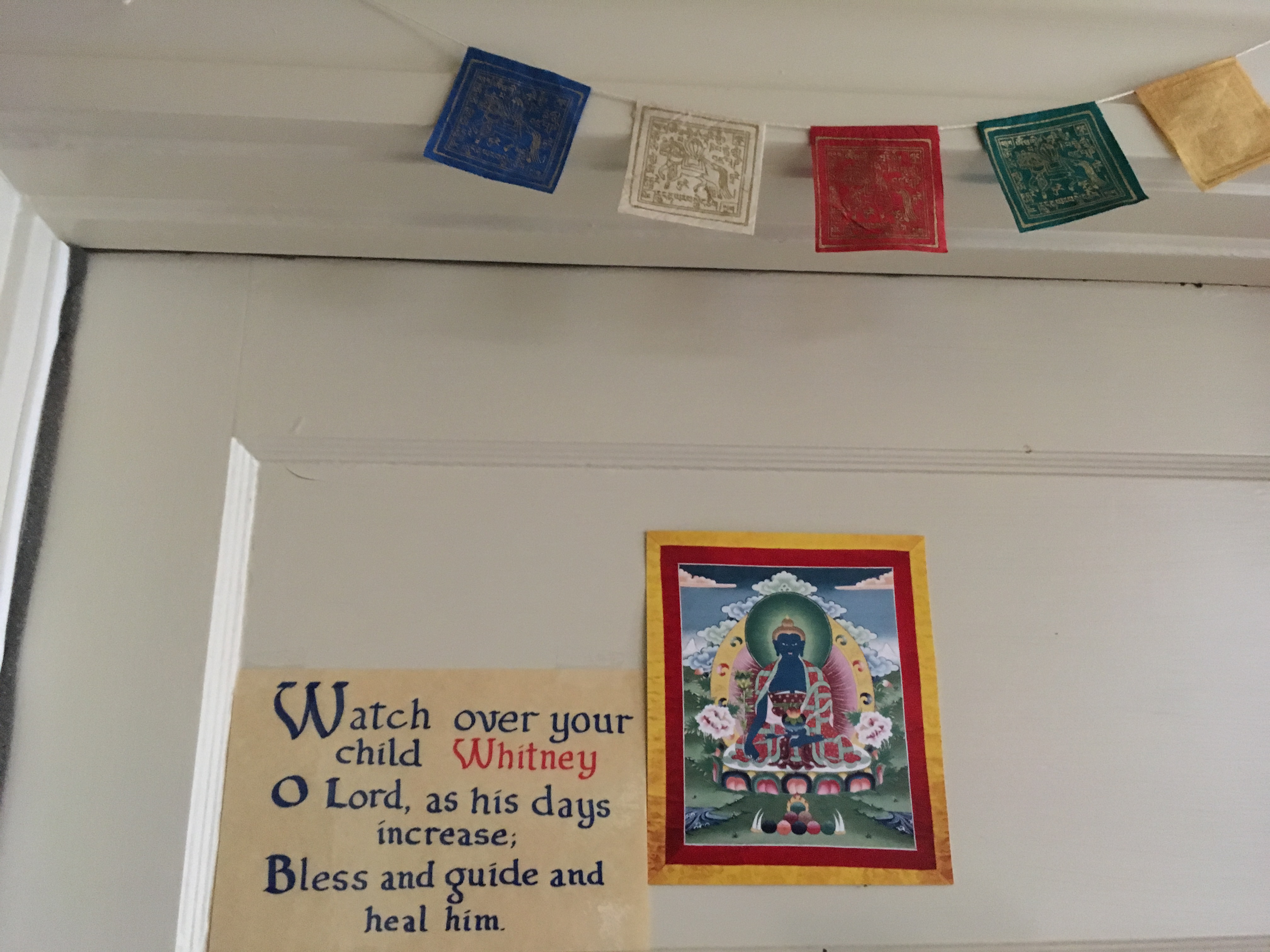

I told someone about the time Whitney and I had together recently, and said it was the perfect summer romance. “He can’t tolerate anyone being in his room,” I tried to explain. “He’s too sick. He’ll crash if his brain is forced to process who I am and why I’m there and he’d go into a vegetative state. His body would shut down.”

“He can’t tolerate anyone being in his room,” I tried to explain. “He’s too sick. He’ll crash if his brain is forced to process who I am and why I’m there and he’d go into a vegetative state. His body would shut down.” I barely understood the science of it, or how it worked. The only way I could think of explaining it was that, even though he’d spent most of his time lying in bed for the last three years, it was more like he’d been resting with his eyes closed.

I barely understood the science of it, or how it worked. The only way I could think of explaining it was that, even though he’d spent most of his time lying in bed for the last three years, it was more like he’d been resting with his eyes closed.

The footage is a little grainy, and the light is dusk. We are standing next to the caribou pen. I am wearing his college sweatshirt, and Whitney is interviewing me. He mentions that it’s near midnight. When he speaks in the video, there is a fluttering of memory and love and grief in my chest. I’d forgotten how deep his voice was.

The footage is a little grainy, and the light is dusk. We are standing next to the caribou pen. I am wearing his college sweatshirt, and Whitney is interviewing me. He mentions that it’s near midnight. When he speaks in the video, there is a fluttering of memory and love and grief in my chest. I’d forgotten how deep his voice was.

In the video, he gives me the camera and I follow him into the caribou pen at the Large Animal Research Station, where he’d been working as a photographer all summer. I left the camera focused on him while he knelt down, and fed a small group of caribou some mossy snacks.

In the video, he gives me the camera and I follow him into the caribou pen at the Large Animal Research Station, where he’d been working as a photographer all summer. I left the camera focused on him while he knelt down, and fed a small group of caribou some mossy snacks. In the caribou pen, he put his face close to some yearlings, nearly touching their noses with his lips. The video ended with him holding the camera as he lay back in the grass, several caribou sniffing at him, hoping for more treats.

In the caribou pen, he put his face close to some yearlings, nearly touching their noses with his lips. The video ended with him holding the camera as he lay back in the grass, several caribou sniffing at him, hoping for more treats.